FREE CHAIRS!

I found a hundred free chairs

today, while walking from my

motel room to a knockoff

Starbucks. These weren’t

chintzy aluminum

folding chairs, but

fully-loaded, cushioned

armchairs—some with

stains—upholstered in

textured marmalade chenille.

They were really free,

with a sign which read

“FREE CHAIRS!”

out front, that slipped,

rotated ninety degrees,

and is the only reason,

to my mind, that they were all

still there, on the patio

of the downtown Billings DoubleTree.

I thought, for a few strides,

about the many people who

had sat in those chairs

through the years, at

wedding receptions,

optometry conferences,

wakes,

and what stories

the chairs could tell,

but soon got overwhelmed,

and anyway I don’t have

space for even one

free chair.

Disturbing the Peace

Even here, where terriers lag,

their liquid tongues lengthening

towards the grass,

as the shade of catalpas

slides across lush acreage;

even here, amidst muted cheers

for a field goal,

above the shuffle of shoes

aslant a soft lawn at dusk.

Atop the 60-hertz hum of cicadas,

rumbles the crushing current of

rubber across pock-marked pavement,

the sandpaper shift of a school

bus’s transmission,

the skitter of gravel, pealing

behind a rusted ‘96 Saturn SL,

the idling ComEd rig, slouched in an alley,

the scrunch of hubcaps on curb,

the metal-on-metal scrape

of the dumptruck’s brakes, the

bravado of Boeing 737s—sharpening

their approach—one after another,

every thirty seconds, or

the scissory swell of a whirlybird

chopping towards the Edens.

Every silence strangled.

America Answers

So sorry you’re dead

to the Murdered Children of [Insert Latest School Shooting Location Here]

So sorry you’re dead.

Prayers up for your family.

It wasn’t the guns though.

It was the guns.

It wasn’t the bullying.

It was the bullying.

It wasn’t toxic masculinity.

It was toxic masculinity.

It wasn’t the gun lobby.

It was the gun lobby.

It wasn’t social media pressure.

It was all the social media pressure.

It was the guns.

It wasn’t the guns—we need MORE guns.

It was the lack of mental health resources.

It was the lack of background checks.

It was a failure of parenting.

It was violent video games/movies/television.

It was just boys being boys.

IT WASN’T THE GUNS.

IT WAS THE GUNS.

It’s the spineless senators.

It’s the feeble leaders.

It’s the Second Amendment.

It’s your problem, not mine.

It wasn’t personal.

What’s new on Netflix?

You Can Tell an Awful Lot About a Guy from the Shape of His Vehicle

I ran the Avalon into the ground one month after quitting my day job as a government bureaucrat. I rode the Amtrak back to Fargo to explain myself to Dad. I was rambling, like usual, trying to tell him why it was so important for me to leave a good paying job — with benefits — to sign up for Yoga Teacher Training.

Dad and Grandad conspired to surprise me with my first car when I was fifteen. Under Dad’s guidance, Grandad scoured the Fargo Forum classifieds for weeks looking for a practical used model. Grandad must have loved this — in retirement, he made a hobby of buying inexpensive used vehicles, fixing them up, and reselling them to make a bit of money. Every time I saw him, he was driving a different car. Ultimately, he and Dad made a decision together and finalized the sale.

We were living in Minot at the time, and Dad somehow enticed me to spend a weekend traveling to Fargo with him. I was in my punk phase then: pink hair, pleather pants, safety pins in my ear, studded dog collar. At fifteen, I didn’t have time to go visit my grandparents. I was too busy plotting the important details of my immediate future. My band, The Atomic Snotrockets, had an upcoming gig, so I needed to rehearse on Friday night. My heavy-petting partner and I were getting together to watch X-Files on Saturday. There was homework to cram in at the last possible moment Sunday night. Nevertheless, Dad coerced me to ride along for the five-hour drive from Minot to Fargo. We pulled up to Grandma and Grandad’s place. Parked in front of the house was a robin’s egg-blue ’84 Volkswagen Golf with vanity plates: 4-BUDDY, my parents’ nickname for me. There’s a photograph somewhere that Grandad took of me opening my car door for the first time. I have a huge grin on my face. I never smile in photos.

Six months later, Mom came downstairs and tapped on my bathroom door as I was getting ready for school. “Buddy,” her voice wavered as she laid a hand on my shoulder and told me that Grandad had died in his sleep. I felt my knees tremble. “I think your dad could really use a hug right now.” It was the only time I have ever seen Dad cry.

Seven years after Grandad passed, I was living in Charleston, South Carolina, and getting ready to move to the west coast. Dad flew down to help me make the cross-country road trip. I had plans to trade in my purple Chevy Cavalier for an Acura Integra coupe. It was a sexy, silver two-door with a spoiler. The interior leather was glossy and black. It had a five speed on the floor and a booming sound system with a Rockford Fosgate amplifier and two twelves in the trunk. Dad calmly guided me towards a more practical choice: a forest-green, four-door Mazda 626. It was the polar opposite of the Integra. The interior wasn’t shiny black leather, but boring beige polyester. No sound system — not even a CD player. The 626 had a stock AM/FM tuner and a tape deck.

Dad and I drove the 626 from the South Carolina Lowcountry to the Puget Sound, where I would live for three years. I drove the Pacific Coast Highway from Seattle to San Diego and back in that car, windows down, playing the mixtape I made specifically for the journey. I folded down the back seat and slept in the 626 along the side of the highway there in the shadows of the towering redwoods near Crescent City. I made a second cross-country trip in that car when I moved to Virginia Beach in 2005, and put more miles on it when I finally settled in Chicago in 2007.

The 626 was the only car I ever paid off. I remember getting the title in the mail from my bank, after paying off the loan. The paper was ivory card stock, with purple purfling in the margins and an official-looking watermark from the bank. I framed it and hung it on the wall. Eventually, the transmission went out and I had to have it towed to a junkyard.

After Dad retired, he started wheeling and dealing used cars. An expert haggler, he’d buy them for cheap, fix them up a bit, and resell them for a slim profit. These were not major overhauls; he wasn’t investing in dilapidated ’57 Chevy Bel Air hard-tops and restoring them. He’d buy dependable, modern cars which had a track record of longevity: Camrys, 4Runners, Civics. He would detail the tires, wax the hood, Armor-All the seats. It was a hobby.

A while after my 626 broke down, Dad surprised me by showing up in Rogers Park. I was celebrating my third year in Chicago and it was the first time he ever visited me there. The second and final time would be for my wedding. He pulled up in a used 2002 Toyota Avalon and handed me the keys. I couldn’t believe it. I drove that car for four years. I could never tell if it was grey or light blue; its color was mercurial, like Lake Michigan. Avalon — it reminded me of that Roxy Music song of the same name. I could almost hear Bryan Ferry singing it — and your destination…you don’t know it.

At some point, the Avalon’s trunk latch broke and I had to keep the lid tied down with bungee cords or it would fly up while driving. One headlamp burned out and I never got around to replacing it. The check engine light was perpetually on. Then one day, the low oil warning light lit up on the dashboard. Dad had taught me to check my oil each time I filled up the gas. I didn’t, of course. After a few days of this light staying on, I bought a quart of oil and poured it in. Things would be okay for a week or two when the light would come on again and I’d repeat the process. I tried to remain optimistic, but my stomach twisted every time I started the car and saw that ominous light on the instrument panel. I was recently unemployed, and couldn’t afford to pay an ungodly sum of money to fix it, so I kept buying a quart of oil at a time and pouring it into the car. One day I flicked the ignition switch and it wouldn’t turn over. The low oil light had been illuminated for several weeks by then. I shouted in frustration and pounded on the steering wheel. I had it towed to a nearby mechanic where they told me the oil pan had cracked which led to the engine seizing up because it wasn’t getting the regular oil supply it needed. CarMax gave me two-hundred bucks for the vehicle. They told me they were going to “part it out”.

I ran the Avalon into the ground one month after quitting my day job as a government bureaucrat. I rode the Amtrak back to Fargo to explain myself to Dad. I was rambling, like usual, trying to tell him why it was so important for me to leave a good paying job — with benefits — to sign up for Yoga Teacher Training and pursue my nascent, albeit outlandish dream of opening a non-profit yoga studio for veterans. He didn’t bring up the Avalon, but he looked worn out. “What about saving for retirement, Son?”

“Retirement!” I scoffed, “My generation doesn’t get to retire.”

Later that week, I hailed a 2 a.m. cab to the Fargo Amtrak depot to wait for the Empire Builder line to Chicago. I had just taken out my pen to work on some YTT homework when the depot’s lobby door swung open. I was dumbfounded to see Dad walking towards me with a thermos at three in the morning.

“I thought you could use a coffee,” he said. “Hold this. I’ve got something in the car.” He carried in three bags of groceries for my twelve-hour journey. Alongside the bananas, granola bars, and bottles of Vitamin Water, he had picked up a fresh six-pack of Hornbacher’s Peanut Butter rolls — my favorite treat from back home. He sat down next to me and opened up his wallet, handing me several bills. “Here. I want you to take this for the trip, in case you get hungry.” I shook my head, but I knew refusing was impossible. We chatted there for about an hour until I had to board my train. As the Empire Builder lurched forward, I watched, with tears in my eyes, as Dad got into his clean, always-properly-maintained truck and drove away.

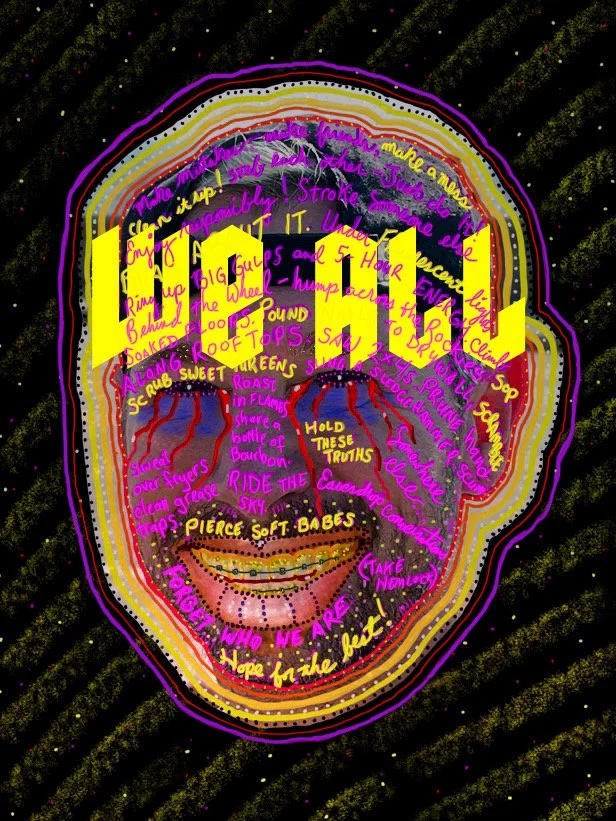

We all

We all agree the Olmecs were the best

We all are made of comets.

We all make mistakes, we all make friends, we all make a mess, we all clean it up.

We all stab each other in dark alleyways for twenty-nine bucks and a transfer.

We all just do it. We all enjoy responsibly. We all think outside the bun.

We all stroke someone else’s kitty behind the ears. We all brag about it later to our friends or anyone who’ll listen.

We pace under fluorescent lights. Behind bulletproof glass, we ring up Big Gulps and cellophane-wrapped BLTs.

We swig 5-Hour-ENERGY and climb behind the wheel of big rigs for an all-night hump across the Rockies.

We pull semen-crusted sheets from hotel beds, replenish minibars, sop up soaked bathroom floors.

We pound nails into drywall, scramble along rooftops—sometimes falling. We saw two-by-fours to the centimeter.

Our fingertips prune from holding our hands under scummy dish water, scrubbing sweet and sour sauce from tureens.

We all buy houses we can’t possibly afford. We all make five figures. We all call out sick. We all default on our credit cards.

We all know how to sling a sledgehammer.

We all could win a Grammy. We all belong in Cooperstown. We all died on the Titanic.

We all would love a Toblerone—if you’re offering…

We all roast in the flames of a fire we all built. We all share a bottle of bourbon by that fire when we should be at home with hubby.

We hold these truths to be self-evident.

We mop the corridors, flanked by aluminum lockers, keyrings jangling from belt loops, wishing we were somewhere

else—someone else.

We sweat over boiling fryers and clean grease traps under deep sinks while the moon rides the sky.

We eavesdrop on our fares’ conversations as they pierce our soft bellies with golden spurs.

We breathe in the melon musk of tear-free shampoo as we bathe our babes at the close of day.

We forget who we are. We forget who we were. We forget who we were supposed to be.

We all take hemlock when the moment arrives.

We prepare for the worst.We hope for the best. We wish we had more time. We

My Ass Rides In Naval Equipment

I should’ve just gone over to the house for this conversation, for Christ’s sake. I only lived a mile and a half away.

I had been staring at the cordless phone in the corner of my cramped bedroom for over an hour, cracking my knuckles and scratching my hairless chin. Finally, I closed my eyes, took a deep breath, and pressed the digits into the keypad.

One ring… two rings… Maybe he’s not home… three rings… A wave of relief started to wash over me. I couldn’t leave this in a message, but this will give me more time… four rings… Yello! A familiar voice warmly barked.

Hey, Dad. My heartbeat thundered in my throat. How’s it going?

Just finishing up my lunch break, Son. What’s up?

I should’ve just gone over to the house for this conversation, for Christ’s sake. I only lived a mile and a half away. Sweat rolled down my rib cage. Well, Dad, I just wanted to tell you…

Three months after graduating high school, I decided to get my own apartment. Not because our home was crowded. Not because my family and I didn’t get along — we did, at least as well as parents get along with their teenagers. Deep down, I think I wanted to prove to them that I could make it on my own, even if that meant working seventy hours a week as a night stocker at Marketplace Foods and a Whopper flipper at the Dakota Square Mall food court.

Most of my co-workers at the mall Burger King were high schoolers or recent grads like me. Karen Knudson was in her mid-fifties. She was a farmer’s daughter. In her teens, Karen married a neighboring farmer. They had several children who helped out on the family farm. In Karen’s mid-fifties, with the child-rearing over and the farmwork passing down to her adult sons, she decided to trade her pig whip for a french fry scoop.

It came up in conversation one Saturday after the matinee rush had ended and the food court was clearing out that Karen had never traveled outside the borders of North Dakota. What do you mean? I sneered, loosening my spiked pleather dog collar, Not even on vacation?

Karen folded her arms in front of her grease-stained apron as she waited for Order 456 to retrieve his Double Whopper with cheese meal. Nope. You can’t go on vacation when you have cattle to mind and fences to mend. She squinted at me like she wanted to say something more but held her tongue.

I regarded her over the top of my Buddy Holly-framed, yellow-tinted glasses, So you’re telling me you’ve never been outside the state? Not even once?

At a tender twenty, I had traveled beyond the borders of my home state, but never far. Dad’s idea of a vacation was spending a long weekend at Gram and Grandad’s fishing cottage in western Minnesota or hunting pheasants in northwest South Dakota. I once took a day trip to Winnipeg to shop with a high school girlfriend. But honestly, in fifty-something years, Karen had never been outside the borders of the Prairie State?

As I was throwing Karen a pity party she didn’t ask for, her beller brought me back to reality. Josh! I’m still waiting on that King-sized french fry!

This information ate at me over the ensuing days. During my night shift at Marketplace Foods, I spilled Karen’s guts to Nat Tanu, the Nepalese stock clerk with one hand. On hearing the news, he turned to me, eyebrows raised, box-cutter clenched between his teeth, and gasped “REALLY?” before dropping a jar of sauerkraut on the floor. It shattered instantly, raining down a hellish odor of rancid cabbage and vinegar so potent that Rob from produce ran over to see what the stench was.

Really.

I had no intention of living in North Dakota my entire life, but I had no exit plan either. Joyce, the gal I was dating at the time, wasn’t that into me. In fact, while I was helping Nat mop up the sauerkraut spill in aisle four, she was banging my best friend Ricky in the back room of his mom’s trailer home. At the time, I was living vicariously through my older sister, Lara. She had interned for a congressman in Washington DC, crashed for six months on a houseboat in Barbados, and at times called Colorado Springs, San Diego, and Whidbey Island home. I wanted a life like that.

My career plan was an enormous question mark. I envied classmates who had their undergrad, graduate, and even post-grad education already plotted out like stars in the Big Dipper. I had successfully finished two semesters at Minot State University but hadn’t yet declared a major. How was I supposed to know at twenty that a career in Arts Administration or Music Ed would still challenge and fulfill me at sixty?

I spent a few restless weeks ruminating over Karen’s situation. One day, during my half-hour lunch break, buzzing on NoDoz and Surge to keep awake, I followed my feet to a sleepy corner of the Dakota Square Mall. The Armed Forces recruiting offices were all dark and deserted on that weekday afternoon, with the exception of the Marine Corps office. I didn’t go in. I stood outside the office, admiring the sharp royal blue uniform on the mannequin in the window — the brass globe and anchor gleaming at the collar points, the blood-red stripe down the pant legs, the pristine white gloves on the mannequin’s hands — and I caught a glimpse of my reflection in the glass. Spiky hot-pink hair jutting out from under my BK visor. A silver hoop perched in my left eyebrow, two gold studs in my right ear, a safety pin dangling from the hole in my left. My purple polo shirt with the Burger King logo stitched into the breast was filthy, reeking of stale grease: an odor that never washes out.

I reached for one of the recruitment pamphlets and pretended to read it until one of the Marines came out to greet me. The recruiter scanned me — toe to tip — with a puckered mouth. His ramrod posture made me stand up a bit straighter. You ever consider signing up, kid? The Corps will make a man of you. I could see my reflection in the polished gloss of his boots.

Hmm, I don’t know. My dad was a Marine. Two tours in ‘Nam. Late sixties. Da Nang. I didn’t talk like this; Dad did. His history was sneaking through my squeaky windpipe.

The recruiter’s deeply sunken eyes were laser-focused on my ear lobes. No shit? Tell your pop Semper Fi. I can get you some more reading material if you’re curious. He shoved a few tri-fold pamphlets into my soft hand. I nodded to him, and as I turned to leave, he stopped me. Woah woah! Wait a second, kid. I turned around as he approached me. The creases in his khakis were sharp enough to draw blood. About face! he ordered. I stared at him blankly. It means turn around. Turn around…please. I felt him tug my shirt collar down. Plunging a fat finger into the back of my neck, he whistled. Ooh wee, what in hell did you get that tattoo for? I chuckled, getting ready to explain its origin when he cut me off. Sorry, kid. The military’s a no-go for someone with a visible neck tat. It’s against UCMJ regs.

UCMJ…? I trailed off. Oh well, it was a dumb idea anyway.

As I walked back to finish my afternoon shift, I could feel my face reddening and a damp warmth spreading across my upper back. My heart was fluttering from the massive dose of caffeine I was on. Back at work, I went into the deep freeze alone and pummeled a box of frozen Whopper patties until my knuckles bled, thinking about that shriveled, insulting jarhead. For perhaps the first time ever, I was feeling self-conscious about my life choices.

The seventy-hour workweeks were grinding me into a coarse powder. My roommates Brock and Dave were on another planet. I would come home completely exhausted from back-to-back shifts to find them throwing marijuana parties. People were over day and night, watching action movies in my living room or playing electric guitar in the basement. Once, arriving home and desperate for rest, I found a girl I didn’t know passed out on my futon, half-naked, in a puddle of Coors Light.

The summer marched ceaselessly onward. I was still popping caffeine pills and barely functioning at either of my jobs. Was it night or day? I rarely knew. After a closing shift at Burger King, followed by an all-nighter at the grocery store, I woke up in a flop sweat, yanked my smelly BK uniform out of the dryer, and sped up the 16th Street hill, the summer sun slanting at an unnatural angle. I parked the Civic hatchback, ran through the restaurant’s back door, and punched in. I apologized to my assistant manager for my tardiness.

Josh — what are you even doing here? Jolene wiped cookie crumbs from the corner of her mouth and pulled the schedule off the wall. You’re not working until eight.

Yeah, it’s 8:20, Jolene! She shook her head and showed me the schedule.

Eight AM! As in tomorrow morning! My head was spinning. Jolene cackled at me. Go home and get some sleep, Josh.

I looked at my watch. There was no time for rest as my grocery store shift was starting in under two hours. I hopped back into the Civic and drove a mile to the outskirts of Minot. I looked out at the endless prairie: knee-high tan grasses, dusty gravel roads, a fumey combine. I saw quiet railroad tracks and listened to humming power lines.

I didn’t see a future. I wanted to smell the ocean. I wanted to feel the rumble of a subway under my feet. I wanted to run.

The next afternoon, finally drifting into the sleep of utter exhaustion, I thought about a book I hadn’t seen in years. It was a hardbound boot camp yearbook Dad showed me once when I was in grade school. A striking, strong young man in short sleeves and cargo pants burst out of the book’s glossy black and white pages: marching in ranks, posing with an M-16 in a helmet and head-to-toe camo. Seven-year-old me looked skeptically back and forth between the images Dad pointed to and the man before me who was in his mid-forties and balding with a beer gut and a bushy salt and pepper beard. That’s me poundin’ the hell out of some poor sum’bitch with that big damn, oh whatchu call it, Joust? Baton? Some damn thing. Oh, and here’s me again, going over that obstacle course wall at Camp Pendleton… he nodded. Now, wouldn’t you want to be a Marine, just like your Pop someday?

No, I flatly told him. I want to stay at home and cross-stitch with Mommy.

Mom cheered and bent down to squeeze me. That’s my boy!

Dad sighed deeply and tucked away the book.

Dad’s time in the Marine Corps was something I was aware of but never openly discussed. Like Dad’s memories from those years, that book would remain locked up in his varnished oak gun cabinet for most of my youth, next to his twelve-gauge Remington and a thirty-ought-six.

Grandad was in the Army Air Corps in World War II. My uncle Arlo was a Marine pilot in Vietnam and another uncle, Larry, was a Vietnam vet who served in the Navy. My sister Lara was in the Air Force National Guard, and my brother-in-law Tim was a Navy yeoman. As a straight edge, anti-authority, hardcore punk kid, I had never even entertained the option of a military career.

My high school years were turbulent, and there were many times when my behavior was outright humiliating. Like when a girlfriend and I — bored and wielding Sharpies — graffitied the entire ceiling of my first car with colorful phrases like “no war but the class war” and doodles of dicks and daisies. Dad took away my driving privileges for two months after that stunt.

Or the night when Dad went into a closet in the basement looking for his winter hunting clothes and discovered a gravestone that read DAD. My bandmates and I thought it would look “punk as fuck” as a prop on stage at the next Atomic Snotrockets concert. The following day, a yellow sticky note was affixed to my bedroom door: “Son, no questions asked. Get RID of the headstone! — Dad”.

Then there was my cricket farm, nipple piercings, screamcore rehearsals in the basement… Maybe it was the Hail Mary of redemption, but the hope of winning Dad’s pride held extra sway over my decision. The next day, I walked with urgency back to the recruiters’ offices, hoping the Marine had the day off.

He did. I proceeded to the Navy recruitment office. I asked the sailor behind the desk if neck tattoos were allowed in the Navy. He dropped a half-eaten Big Mac onto his paperwork-strewn desk and slid it away. Let me take a look, he said. As he approached me, I could see greasy thumbprints smearing his spectacles. That? That’s nothing. Your shirt collar would hide most of it. He wiped his hands on his wrinkled uniform pants. Take a seat, young man. You ever heard of the ASVAB?

A few days after taking the military entrance exam, the recruiter called me up. Congratulations. You did well enough on the ASVAB to be a Nuke if that’s what you want. I had no clue what that meant or what I wanted. I said yes. He told me the next step was enlistment. As soon as next week, I could raise my right hand, swearing an oath to support and defend the Constitution of the United States. He asked me to think about it.

I thought about it. I didn’t discuss it with anyone else. My future started to crystalize over the next few days. I could leave North Dakota. I could have money for college, and since I didn’t know what I wanted to major in, I’d have time to think about it. I could continue the family military tradition. Dad might be proud of me.

So there I was, calling to give Dad the news, rather than just driving a mile and a half to the house.

Well, Dad, I just wanted to tell you…that I’m enlisting in the Navy next week. Silence. I pressed my ear to the receiver. Had he hung up?

Dad…?

Uh, say that again, Son? To hell are you talking about?

I told him the whole story about first meeting the Marine recruiter and getting rejected. Thinking about it, going back, speaking with the Navy recruiter, and taking the ASVAB. I told him it made sense since I would get good experience and money for college. I didn’t tell him about the pride.

Have you told your mother yet?

No, Dad, I thought you could break the news to her.

Oh yah, he laughed. Thanks a lot! I couldn’t read him. I should have just gone over to the house. Well, Son, I never thought I’d live to see the day where you joined the military, but I always thought if you ever did enlist, God help you if you joined the Marines. Pick the Navy or Air Force. They don’t do a goddamn thing anyway. Safer.

I laughed. Yeah, I guess.

Well, you comin over for supper on Sunday?

Yeah, Dad, I’ll be there.

Ok then.

I hung up the phone, sat on the corner of my futon, and cried.

Sniper

“Let’s see. You got the safety on now?” He leans over the shifter and checks my gun before finishing his sentence. He smells like rifle oil and Irish Spring. “Good man.” His right hand floats from my rifle to the radio’s volume knob, turning the AM golden oldies station to a low murmur. His hand lands on his thermos. Steam escapes from the opened lid as Dad takes a sip of the Motel 6 Folgers.

A good hunter only needs to fire three rounds.

Dawn has barely broken, and the floorboards of Dad’s usually immaculate Toyota pickup are already littered with Styrofoam coffee cups, the slimy shells of sunflower seeds, and polished brass thirty-ought-six rounds. Dad’s left wrist rests at the top of the steering wheel as the tires skip across scoria roads, kicking up a coral-colored plume in the rearview. His head is cocked perpendicular to his shoulders, scanning dark patches on the rolling plain.

“You watching that side, Sonny?”

I grunt in assertion, gripping the little rifle between my legs. I’m still asleep. This is many years before I will start voluntarily waking up before sunrise. Looking for something new to pop into my Walkman, I open the center console and run my finger across Dad’s cassette collection, unchanged in a decade: Jim Croce, Waylon Jennings, Whitney Houston.

“Let’s see. You got the safety on now?” He leans over the shifter and checks my gun before finishing his sentence. He smells like rifle oil and Irish Spring. “Good man.” His right hand floats from my rifle to the radio’s volume knob, turning the AM golden oldies station to a low murmur. His hand lands on his thermos. Steam escapes from the opened lid as Dad takes a sip of the Motel 6 Folgers. His chin is freshly shaved, but a thick salt-and-pepper mustache is perched under his handsome nose.

It’s opening weekend of deer season, and our assigned hunting unit is the highly coveted 4A, a forty-five-minute drive from our motel room in Dickinson. Bordered by Killdeer, Watford City, Grassy Butte, and the Fort Berthold Reservation, 4A is eight hundred square miles of western North Dakota badlands. The unit is cut in half by the Little Missouri, the river that carved these low canyons out of limestone around 600,000 years ago, the end of the last Ice Age and the heyday of Neanderthals. Viewed from 30,000 feet, the dried canyonlands resemble flattened millipedes, whose legs are forested gullies, perfect terrain for Mule deer to find shelter.

In these days before Garmin or Google Maps, I am Dad’s navigator, sitting in the passenger seat, with a worn topographical map of North Dakota flat across my lap. Not that Dad needs it to get around his home state. As Team Leader at the Vet Center in Minot, part of his job is driving around the western part of North Dakota to make house calls to the Vietnam and Gulf War veterans that he counsels. Even on these unmarked scoria-covered county roads, which all look the same, he’s got a sense of direction that confounds me.

Margaret Joe Brown, the family chocolate labrador, is sitting behind us on the narrow bench seat of the pickup’s cab. Maggie is more Dad’s dog than anyone else’s. He has been training her since she was a pup, honing her retriever instincts. She is his bird dog. When we hunt pheasants, she disappears into the fallow corn stalks and flushes game. It’s difficult to train dogs to stay close to the hunting party. Some labs are known to run two hundred yards ahead, well outside of shotgun range. Maggie stays close — within fifty yards — perfect for pheasant hunting. When a member of our hunting party strikes a bird, she always brings it back to Dad, sometimes two birds at a time, to his amusement. She’s smart and efficient. And sweet.

Dogs aren’t needed in deer hunting; it’s usually frowned upon to bring them out. Their scent and their barking can spook the deer. Maggie’s a good girl, though, and she’s a far superior companion for Dad than sixteen-year-old me. She doesn’t complain about Dad’s music selection or his unwillingness to eat anywhere but Applebee’s when we stay in Dickinson. True to her breed, she is the shade of a Hershey bar with a white patch on her chest in the shape of a number seven. Her eyes are deep brown and kind, like Dad’s. She’ll die far too young from a tumor on her liver. The surgery is too expensive, so Dad will opt to put her down.

We cruise along for a while when abruptly, Dad spreads his broad, gloved hand across my chest while skidding the truck to a jarring halt. A plume of pink dust billows around and ahead of us. He looks past me off into the trees, a note of disappointment in his gruff whisper, “Joshua! A monster! Heading right for that goddamn tree line.” I look where his nose is pointing and see only a blur of bald branches and wild grasses.

Dad deftly click-clack-clicks his foot down on the emergency brake and silently springs from the truck. He pulls his 7mm Remington Magnum from the gun rack over Maggie’s head and charges one round into the barrel. He’s preloaded two additional rounds into the magazine. One of his many maxims is: “a good hunter only needs to fire three rounds, any more than that, and he’s poisoning the watershed.” Never taking his eyes off the buck, which I still can’t see, he crouches around the front of the truck and down into a ditch: ever the twenty-two-year-old Marine. I quietly open my door and hop out, crouching low and following him with my thirty-ought-six. We leave the doors open as Dad has instructed. “Don’t make a sound. Mule deer can hear a duck fart from a half-mile away.” He sidles over to a buckshot, sun-faded fencepost and steadies the polished steel barrel of the weapon in his sniper’s hands. He trains his left eye, watering from puffs of wind, onto the bead, and centers the bead onto the beast.

I point the scope of my rifle in the general direction of Dad’s 7mm barrel, only then catching my first glimpse of the buck. Emerging from a dense outcropping of trees, he is indeed a monster. I can see five horns on each side of his antlers — a “five-by-five” in hunting terminology — with the barrel chest of a female elk.

The deer is over a quarter-mile away and moving. I shake my head. The last thing you want to do is shoot him in the hindquarters, destroying pounds of good venison. Given the wind and the distance, Dad will need to aim at the animal’s spine to avoid hitting low. As he’s told me innumerable times, “you don’t want it gut-shot.” That could mean hours of following the blood trail into the deep gulleys of the badlands. Our hunting parties have lost game in these situations before. Jason, a regular member of our hunting party, once delivered a non-lethal shot to a Whitetail buck. We followed the blood trail for hours, over snaggled hills and rocky valleys, finally finding the miserable creature bedding down near a creek. When he heard us approaching, he lifted his head in our direction. The little two-by-two buck’s lower jaw was hanging open. Jason’s first bullet had passed straight through the animal’s face. He now raised his rifle and put the little buck out of his misery, but Dad couldn’t quit laughing about Jason’s mangling of the deer. For years after, that deer would be remembered as “the yaw buck” because it looked like he was yawning when we came upon him. “That was a horseshit shot, Jason,” Dad said afterward, laughing. “Poor little bastard, running across the badlands, mouth hanging open like that.” Dad’s laugh is unabashed; toothy. “Yawww!”

Dad’s ungloved pointer finger rests patiently over the trigger. He controls his labored breathing as he’s taught me: “Wait until you exhale, Son, and then squeeze the trigger, don’t jerk it.” The buck begins to corner away from us. “Just come broadside, you sonofabitch,” he whispers. “Muleys are stupid,” he has told me. “They’ll run away awhile and then turn around and look at you, and that’s when you gotta get ’em. Different from Whitetails. Once you see that white ass bounding away from you, they’re gone.”

Through my scope, I can see the buck’s enormous hindquarters rippling with muscle as he trots away. Three hundred and fifty yards now, nearly out of range. Suddenly, as we half-hope, half-expect, the buck stops and looks back at us over his left shoulder. His large rack turned, radar ears alert.

A powerful blast emanates across the farmland, echoing off the canyon walls for miles. A moment later, the monster kicks his hind legs, runs in a tight, wild circle, and crashes head-first to the ground. He snorts a final, blood-spattered breath, which rises and blows briefly in our direction, before dissipating into the chill November air.

“Yo! Got ‘im!” Dad chuckles, turning to me with his shooting hand up for a high five. We return to the truck to retrieve Maggie and grab Dad’s gutting knife. He takes another satisfying sip of cheap coffee, and we go to get the deer. Maggie trots ahead, nose to the ground, as we cross the shorn wheat field and find the monster muley, stone dead. Dad lobbed a perfect shot, just behind the left armpit, straight through the heart. There are no pink bubbles around the wound, or the buck’s muzzle, which would signify a lung shot and a slower death — while the animal drowned in his blood.

It was a heart shot: clean, fatal, and made with only one round.