Evolution of a Coffee Snob

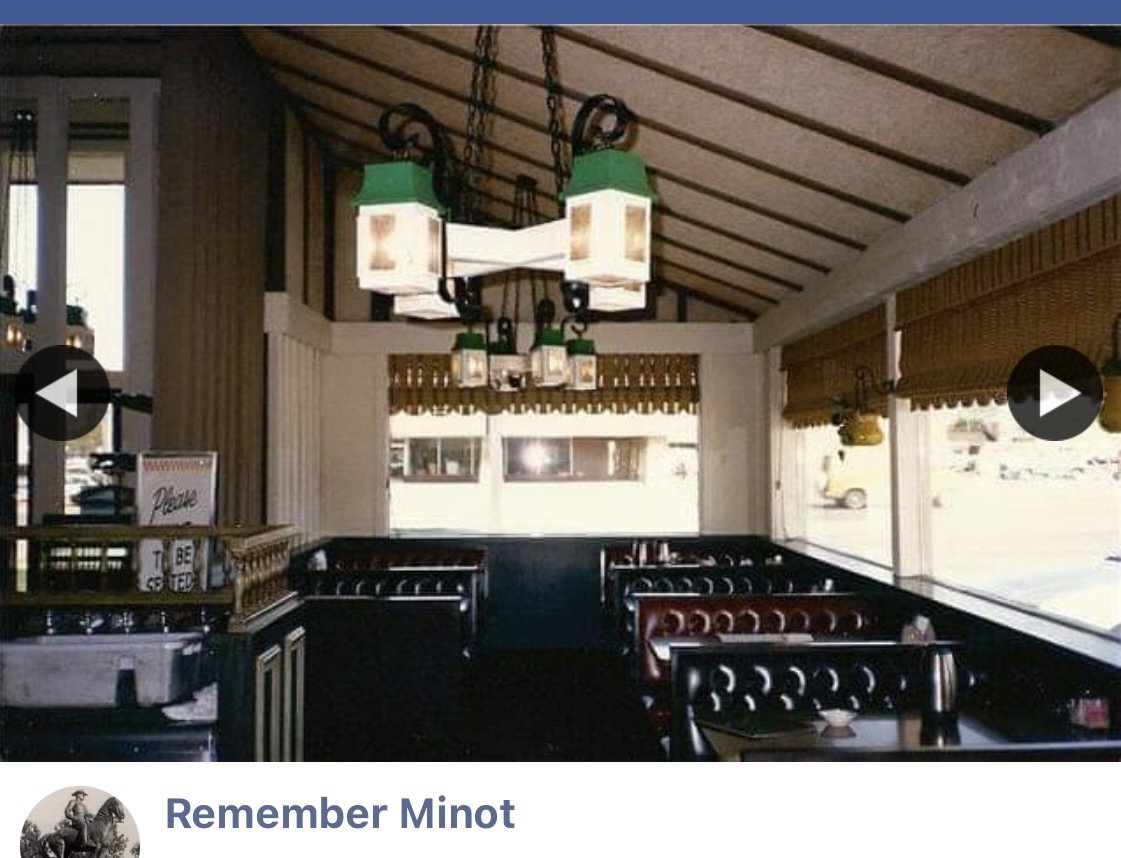

1996, Minot

I’m sixteen, at Ryan’s Family Diner, where coffee costs fifty-nine cents (including unlimited refills). It’s after ten on a Friday and I’ve just come from the Fitz of Depression concert at Minot’s Collective Cultural Centre. A smoldering Djarum Black rests between my fingers. The butt matches my painted fingernails. My hair is bleached the color of the snow that’s piled on the windowsills of the diner. I stir two sugar packets and one room-temperature Land-o-Lakes creamer cup into a mug. The coffee slowly fades from mud to cardboard. The chintzy clink of a teaspoon along the ceramic walls of the cup blends with the clattering of plates that busboys load into plastic tubs. I lift the steaming brew to my lips and sip. I can feel the stares of the squares surrounding me as I scribble onto a napkin what I’m sure is a masterpiece:

Heathenistic hell flames!

burn at me! lap at me!

lift me and digest me once more

squeeze my juicy, rotten fruit, oh lord!

Ryan’s Family Diner, Minot, ND RIP

1998, San Diego

I’m visiting Lara after high school graduation. She’s at work when I decide to explore the city. First order of business is to find a coffee shop—one she recommended, called Starbucks. I order a grande (that’s what they call a medium) drip coffee and am thrilled to discover shakers of cinnamon, chocolate, and vanilla powder near the trash bins. There’s a park out front of the Starbucks where an ambulance is loading a dead vagrant onto a gurney. I stare for a while and then tote my coffee around the neighborhood, in search of a record store I found in the yellow pages. I purchase ska band Hepcat’s “Scientific” and pop the cassette into my Walkman as I bop among palm trees. I walk close to ten miles, stopping off to get my tongue and eyebrow pierced on a whim. Later that day, I tell Lara what I did all day and her eyes fly open. “What the hell, dude? Mom’s gonna kill me!”

Lara and me in San Diego, 1998

2005, Persian Gulf, near the Strait of Hormuz

I roll out of my rack just before twenty-two hundred hours, pull on my poopy suit and stumble down the p-way to the aft galley. I approach the coffee canteen and fill up a styrofoam cup with lukewarm sludge, before climbing down the ladder to the bowels of the ship—the Reactor Compartment. I relieve the mid-watch, settling onto the operator’s chair. I run my gaze across the board. Dozens of dials, meters, LEDs, warning lights, buttons, and triggers stare back at me. I pray to god that nothing out-of-the-ordinary will happen over the next six hours and take a long stinky pull from my cup. Having taken my hourly logs, I flip to the last page in my clipboard, where I’m writing what I’m sure is a masterpiece:

Blue sky, blueberry,

Blue sea,

bluer than Robert Johnson

2007, Brisbane

I wake up at a bed and breakfast outside Brisbane on Lacey & Adam’s wedding day. Breakfast is served outdoors on a sunny patio, in the shade of sweet viburnum. We have warm bialy rolls with Vegemite, orange wedges, and a French press. I pour myself a small cup and taste coffee like I’ve never tasted coffee before. I catch flavors of blackberry, pine nuts, and somehow, honeysuckle. When I get back home, I throw out my Mr. Coffee and never look back.

2014, Edgewater

The best part of my day is early morning. I bike down to Coffee Studio on Clark and Olive. They make the best coffee in the city, I’m sure to tell anyone who asks. I order a single-origin pour-over and a red velvet donut. I sit on the sidewalk and watch the buses and cars stalled bumper-to-bumper. It’s early September and there’s a crispy chill in the air, though it will heat up by midday. It takes five minutes before the barista—Clarice, a clarinetist—calls my name. The oversized mug is filled all the way to the top and the deep brown liquid has a sheen on the surface. Lacy ribbons of steam rise up out of the mug. I slowly bring the coffee to my lips and sip. This moment makes the rest of my day, processing timesheets at the Illinois Department of Rehabilitation Services, feel a little easier. I pull out my notebook and compose what I feel is my masterpiece:

The entire goddamned globe is always

within arm's reach, now.

Our once-beautiful faces

seared in a pale blue light--

dead dahlias drooping in a stiff autumn breeze

2021, Horner Park

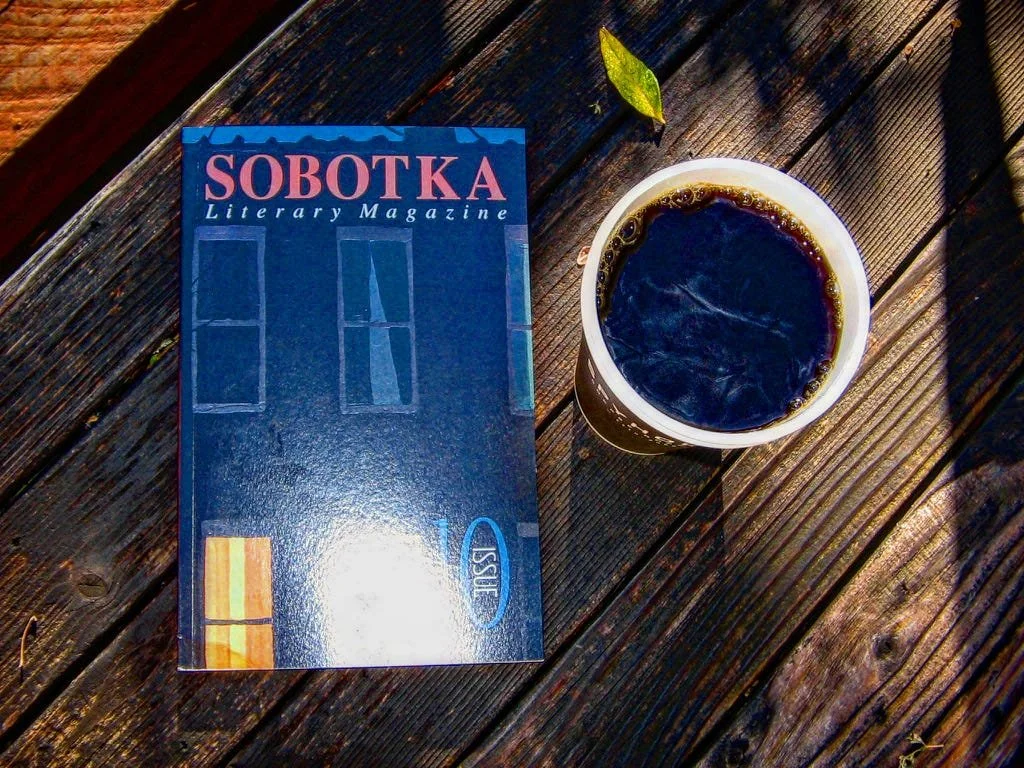

I wake up at five every day, even on weekends. This is my golden hour; the one hour I have to myself before I start getting the inevitable early morning trouble-calls from work. I light the kettle, pour precisely eighteen grams of coffee beans into my burr grinder and press the button. The fresh grounds are of perfect consistency, like dried beach sand. I pop an unbleached circular paper filter on to the end of my aeropress, pour in the grounds, and once the water temperature reaches two-hundred degrees, I bloom the grounds. Steam rises up and I catch the first whiff: rose petals, dark chocolate, mown grass. I pour in the remaining eight ounces of water, stir for thirty seconds and slowly press the plunger into my favorite mug. I take a luxurious sip and gaze out my living room window, past the reflection of my hair, which is turning white naturally now, to see the sun shimmering through the honey locust branches. I open my laptop to a new email. Floating atop the dozens and dozens of rejection letters, I can barely believe the text: “I am delighted to inform you that your poem has been chosen for publication…”

Opus 18, No.4

A pedestrian quartet by Beethoven changed the trajectory of my life.

In the 1980s, my parents owned a Zenith record player. It had a plastic silver face, faux wood-grain sides and a tuner display that glowed lime green when switched on. Mom and Dad didn’t own very many LPs — but what they had was gold. Sam Cooke, the Beach Boys, the Beatles, Marvin Gaye, the Temptations: this was the music of their heyday. There was no Beethoven in their collection, no Miles Davis either. No Public Enemy nor Cyndi Lauper, although Dad did love Whitney Houston and kept a copy of her self-titled debut cassette tape in his vehicle for at least a decade after its release. You haven’t lived until you’ve seen a man with a gun rack in the back window of his truck earnestly singing along to “How Will I Know?”

As I became a teen, my parents’ tastes veered more towards Travis Tritt and Randy Travis: countrified tunes that didn’t connect with me. I was soon taking cues from Soundgarden and Pearl Jam. I started playing bass guitar at fourteen and took bass lessons for a short while that spring. By the end of June, I had worked through all the lessons in The Electric Bass Primer, Volume 1. Ray, my bass teacher at Star Guitar, told me to bring in tapes of songs I liked and wanted to learn and he’d teach me to play “by ear”. Ray rolled his eyes when I brought in Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” and “Love Buzz”. He was able to figure out, play, and begin teaching both songs to me in under five minutes. Kurt Cobain was a tortured genius, but Nirvana’s bassist, Krist Novoselic, was white bread — boring and uninspired. I didn’t realize it at the time, but Ray sure did. The next week I brought in “Heart-Shaped Box” and “Polly”. Ray yawned. A couple of months later, I brought my cassette of Dookie to rehearsal and Ray’s eyes lit up. When he heard Green Day’s “Welcome to Paradise” he smiled: Now, there’s a bassline! Let’s get to work.

My interest in Nirvana and Green Day led me directly to an underground, independent punk music scene that was inexplicably flourishing in Minot, North Dakota at the time. Mid-nineties punk legends like Bikini Kill, Godheadsilo, Fitz of Depression and many others played for legions of enthusiastic spike and leather-wearing teens. At my first band’s first show, on a Sunday night, in front of a half dozen friends, I wore an American flag-bedecked motorcycle helmet, with visor down, as I plunked through the set, playing my janky little bass lines.

A decade later, I was still cranking out janky little bass lines, sans motorcycle helmet. During my time in the Navy, I met a couple of guys and invited myself to play bass with them. We’d play Creedence and Jackson 5 cover songs in the dive bars of the Pacific Northwest, Guam, and Virginia.

As I planned for my impending post-military future, I was also embarking on one of my annual existential crises. I was loosely looking into colleges I wanted to attend, but had no clue what I wanted to major in. If hard-pressed, I would venture only a room-temperature response: “something in music?”

Klickitat County (James Rascoe, yours truly, and Jack Brett), circa 2004

I was fortunate enough to have a bevy of free time — as our ship was in dry dock — and signed up for some general education courses at Old Dominion University. My course-load for my first semester at ODU shows the confusion I held for my imminent future: Physics of Sound, Sailing 101, Intro to Creative Writing, and Music Literature Survey. Of the latter, I had no idea what to expect, I just knew I’d probably learn something about music. As it turns out, it was a history of classical music from the Middle Ages to present. One of the requirements of the class was to attend at least two classical recitals per semester and write up concert reports afterward. That assignment led me to Beethoven, and the rest of my life.

The first concert I attended for the class was in September, 2006 at Chandler Hall on the campus of ODU. The Borromeo Quartet was performing Beethoven’s String Quartet in c minor, Op. 18 №4 along with two other string quartets that I have long since forgotten. The hall was intimate but sparsely-attended. By the second bar of the first movement of Op. 18 №4, I was riveted. I would soon discover that there is nothing inherently groundbreaking about Beethoven’s Op. 18 No. 4. It doesn’t represent an evolution in Beethoven’s own compositional style. It is no “Ghost Trio,” no “Pathetique” Sonata, certainly no Symphony №9. It is nearly lost in the classical haystack that also contains Bach’s perfect cello sonatas, Bellini’s operatic arias, and Chopin’s heart-wrenching nocturnes.

But the sound of that quartet in Chandler Hall was as smooth as a good merlot. Wood paneling projected and refined the unamplified violins, viola and cello. The first and second violinists leaned into the music, swaying with the downstrokes. The violist’s eyes flashed back and forth from the cello to the violins, reading them for rhythm, for changes in tempo. The music built to a galloping, swelling ending with all four strings playing three fortissimo triplets in unison. The sparse crowd waited for the reverberation of the final chord to fully decay before applauding the musicians. I had literally never heard music like this before.

When I walked out of Chandler Hall that night, I knew what I wanted to major in. I wanted to preserve that performance. I wanted to put that sound in a jar, and open it up whenever I was feeling hopeless or lost. I wanted to re-create that concert for anyone who couldn’t attend the recital. I wanted to be a classical recording engineer.

One year later, I was living in Chicago, majoring in Audio Arts and Acoustics, and cold-calling local classical groups to see if I could record their recitals. I was volunteering at the CSO and subscribing to BBC Music magazine. By 2010, I was interning at Chicago’s only classical radio station, WFMT. I worked my way up the ranks, from intern to overnight Production Assistant to Recording Engineer — my goal — before moving up to Operations Manager and finally Chief Engineer in 2017.

I can’t listen to any one genre of music for too long without growing a little tired of it, so I listen to all styles, from Billie Holiday to Amalia Rodrigues to Megan Thee Stallion. But every time I hear the Op. 18 №4, I stop whatever I’m doing and fall back in love with classical music.

Rebel at Heart, Obliger by Nature

In The Four Tendencies, author Gretchen Rubin filters the population into four personality types: Upholder, Questioner, Rebel, and Obliger. To describe the Obliger as “conflict-averse” would be hitting the nail on the head with a hydrogen bomb. Obligers are far and away the most passive of the personality types—these are your silent sufferers. That friend of yours who will change planned weekend getaway to meet you for coffee because you had a stressful week? She’s an Obliger. She may have just lost her arms in a thresher accident, but since she’s an Obliger, she won’t bother you with her own travails, she’ll just nod and listen, wishing she was at home bleeding out in the privacy of her own bathtub. Then she will pick up the bill, because you are such a good friend.

I am an Obliger, by nature.

I am eleven years old. There’s this bully named Geirke. Big ears, bad breath, a foot and a half taller than every other fifth grader. He’s been relentlessly antagonizing my friends and me for weeks. On the playground, Geirke gives me an atomic wedgie. I emit a high-pitched squeal and need to visit the school nurse immediately after. Another day, I’m standing in line at the lunchroom, talking to my secret crush Marissa, when Geirke pulls my sweatpants down around my ankles. I drop my lunch tray in a frantic maneuver to cover my exposed bare ass-cheeks. Tuna noodle casserole, green beans, and chocolate pudding splatter to the floor. Geirke steals plastic straws from McDonalds and then spends Social Studies pelting me in the back of the neck with spitballs he made from moistened pages of his textbook. I silently oblige all Geirke’s bad behavior as a penance—in Sunday School that year, the nuns taught me all about penance. If I didn’t confess my sins to Father Halverson and perform a penance for those sins, I was guaranteed to go to Hell. Getting bullied by Geirke was probably my penance for not cleaning the litter box or for calling the neighbor lady a “cock-whore” that time in second grade.

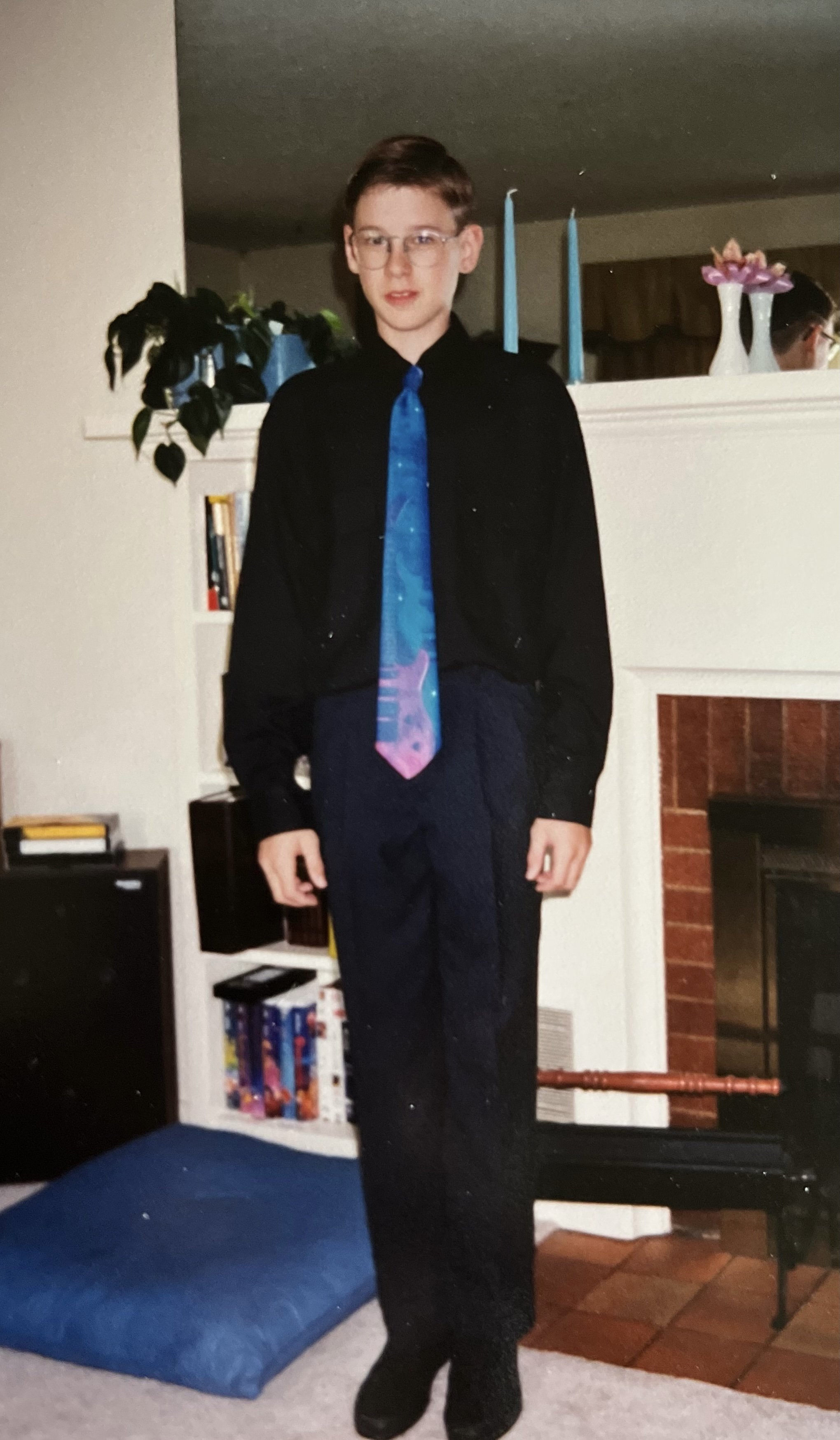

Adolescent Obliger (sauvagicus obligicus) in the wild, no doubt doing an acquaintance’s homework

The Obliger sees their needs as less important than those of others—these are your door-mats, your Iditarod dogs. The Obliger willingly takes on more external obligations than a reasonable person would care to shoulder, but in so doing, often fail to take care of themselves. They eat Taco Bell because they are too busy cooking for others to plan a healthy meal for themselves. They skip the gym because they are too busy reviewing their coworker’s presentation notes. When happy-go-lucky non-Obligers try to intervene—You need a spa day! or I use meditation as a way to ground myself in the present moment!—the Obliger laughs out loud. The concept of having enough time to do something nice for themselves is a riot. “If only there were 36 hours in a day...” they smile wryly, while secretly acknowledging they would spend 35 of those hours obliging others.

I am thirty-two years old and I’m composing the score for a short film, gratis. The director/writer/lead actor calls it a “Western Noir”. The story is bad, the acting is worse, and the music is bordering on maniacal, but I am dedicated to doing the job. I know I will receive no pay, or even recognition for my work, but I am obliged to finish what I started. During the eight months I spend composing, orchestrating, performing, recording, and revising the music, I lose, over and over. I commit to band practices but fail to show up because I’m working on a picture-lock deadline for Savage Noir. This happens often enough that I finally get a terse text from Rob, who is obviously an Upholder: “Sounds like the band isn’t really a priority for you anymore, Josh.” I begin to wonder exactly what my priorities are once my rocky marriage reaches a crevice of no return, culminating in divorce. I can’t even commit to carving out the last half-hour of my day to watch Curb Your Enthusiasm, because I’m too tired from overcommitting. It’s pretty, pretty, pretty…not good.

The Obliger is prone to snapping. These are your glue huffers, your bar brawlers. Granted, as far as brawling is concerned, Rebels are equally as culpable. If you’re looking for someone to break up a bar brawl, locate an Upholder (these are your saints, your Eagle Scouts), or at the very least, a Questioner (your naïfs, your exploitative middle managers). When neighbors later proclaim I never would have guessed she had it in her, or he seemed like such a kind, quiet lad, they’re referring to Obligers.

I am thirty-five years old and I’ve unceremoniously walked out on a promising new career as a government bureaucrat. I’m giving it all up to enroll in yoga teacher training. I picture myself shirtless, on a beach in Belize, leading sun salutations to a group of wealthy British tourists. My parents are both frowning at me from the couch. Sleet pelts their living room window like Geirke’s spitballs pelted my neck in fifth grade. I know this is serious though, because it’s 6:30 and they’ve turned off Wheel of Fortune. This feels like that time in high school when I careened into their driveway behind the wheel of a new Chevy Cavalier I purchased on a high-interest MasterCard. Or that time I told them my first choice, backup, and safety colleges were all in Hawaii.

“What about retirement, son?” My Dad, retired for ten years, pleads (he’s an Upholder).

“Retirement!” I laugh obnoxiously, and for too long. “My generation doesn’t get to retire!”

Boomers. Amirite?

“Well, as long as you’re happy...” my Mom shrugs. She’s an Obliger too.

RUTH

Mom, Lace and I moved back in with Dad in Minot, midway through my eighth-grade year. I played sousaphone in the marching band, wore tee shirts bearing the logo of my previous school, tucked into ill-fitting Lee jeans that Grandma and Grandpa purchased from the Dakota Boys Ranch thrift store. I often tied a long-sleeve flannel around my waist, à la Joey Lawrence’s character (“Joey”) on Blossom. The popular kids at my new school would wait long enough for my back to be turned before letting out a loud, sarcastic “WHOA!” At home, I’d listen to my Boyz II Men and The Bodyguard cassettes, alone in my bedroom.

Even though attending the middle school soirées had been my favorite activity at Dilworth-Glyndon-Felton Junior High, I have yet to make an appearance at any of the Erik Ramstad dances. In Spring, when the eighth-grade formal comes around, I have no intention of attending. On the drive to school one morning, Mom asks me, out of the blue, “Are there any girls you have your eye on?” My face turns red as I shrug and stare out the back seat window. Mom is persistent though, and at some point over the following days, I reveal that I have a minor crush on Ruth, who plays clarinet in the school band. Ruth’s often unkempt hair is the color of the bear pelt in Dad’s den. She has braces and a charmingly self-conscious smile. We have never spoken. There is no overlap between her friend group and mine. In fact, my friend “group” only consists of Aaron, a guy from my Social Studies class who wears a Nirvana Incesticide shirt and doodles in his textbook rather than taking notes.

On the evening of the formal, I am in my bedroom, shirtless in Zubaz and watching Cops on a tiny, hand-me-down black and white TV while playing on a 3D vision board: a “bass guitar” I have constructed from an empty Kleenex box, a cardboard paper towel tube, and four rubber bands. Mom raps on my door and tells me to get dressed up in a hurry—she has a surprise for me. I hear unfamiliar voices in the living room as I don my black silk shirt and a clip-on tie patterned with dueling electric guitars against a neon blue background. As I walk into the living room, I am stunned to see Ruth, who appears as bewildered as I am. I look at Mom and then at Ruth, who stares at our stained carpet. Our black longhaired cat, Circe, rubs herself against Ruth’s bare shins. Ruth takes a pronounced step backwards.

Mom clasps her hands to her chest and coos. “Let me get a picture of you two over by the TV set.” Reluctantly, Ruth comes alongside me. We exchange fleeting, embarrassed eye contact before I return my gaze to my feet. Ruth presses her hands along her knee-length floral-print skirt, and looks up long enough for Mom to snap her photos. Ruth’s dad is idling in the driveway. She sits up front with her dad, while I hop in the backseat. The vehicle is completely silent as he drives us to the school. Once Ruth and I walk through the doors of the cafeteria/gym/dancefloor, she joins her friends and I sit alone in the bleachers, wondering how Mom got Ruth’s phone number.

I never speak to Ruth again.

January 29 Journal Journey

29JAN2025 - I must be the dumbest fuck in my entire circle of friends. Hmm. This is what I have to say after spending an absolutely lovely weekend with my dearest compadres? F that. I had a day off Monday—a whole day to be creative, if I wanted to be—alas, I am a hack. When I have time to be creative, I end up doing something that makes ZERO impact. All the energy I have wasted on music projects. All the time I have wasted writing words that nobody cares to read, or shooting and editing stupid videos for twos and threes of views. Nobody. I am nobody.

29JAN2024 - Brainstorming for Minot Punk Zine/chapbook in the works:

Activities I enjoyed as a teenager

—Walking around Minot, ND with Aaron Davis and Kolin Thompson, before we had vehicles

—Attending shows, getting close to the stage, or back in the peripheries, eardrums ringing through the next morning. Buying tapes, patches, 7”s

—Making friends with my Burger King co-workers. Listening to CDs of the Misfits and Green Day in the back and getting chewed out by our bosses.

—Going to Jon Seright’s home and bleaching each other’s hair while watching Reservoir Dogs or Return of the Living Dead 3

—Playing bass all the time: in bands, alone with cassettes in the basement, in BJ’s parents’ garage and getting the cops called on us for noise

—Making out in RB’s bedroom with Violent Femmes playing on her bookshelf cassette player. To this day, I can’t hear “Blister in the Sun” without thinking about that. She always knew when her mom was coming home because she could hear her Blazer crunching down the gravel driveway. God, her mom was younger then than I am today.

29JAN2022 - It’s been a good week on the writing front. My essay, “The Home Depot Buddha” was workshopped in my Advanced Creative Non-Fiction class on Monday. To a person, they loved it! Some were “astonished by the honesty” in it. Others said they “Feel like it’s a gift to be able to read anything I write.” So many complements! The next morning, my professor, Dr Sarah Fay emailed to tell me she wanted me to submit it to Longreads and other journals. She told me to look in the back of Best American Essays and submit it to at least ten publications listed there, and she would help me write an introductory email! Two weeks earlier, she had praised my classroom presentation, saying she asked me to present first because she “knew I would set the bar high”. I am feeling like an actual writer, lately.

29JAN2021 - Writing, writing, writing…what a week! On Tuesday, I got an email from Pest Control Magazine stating that they had chosen to publish my poem titled “Prey”!! I am so thrilled that something I wrote will finally, for the first time, be in print! It’s been a dream of mine for as long as I can remember, and at long last, it has become reality. Yes yes, perhaps taking a writing workshop via Zoom from the editors of the journal may have improved my standing, yes yes yes, it’s a small, independent, relatively new publication. All of this is true, but it doesn’t take the bloom off the coffee. I am thrilled.

Aside from that, I’ve been working on a new poem and revising other pieces to submit elsewhere. Poetry is a hard gig.

29JAN2020 - Dear Diary, more complaints coming your way! Shocker! I have been in a perpetual foul mood for days/weeks. Work stress has really gotten to me. So much so that I’m actually thinking about other positions available elsewhere. The shit storm never ends. Things are constantly breaking. I’m getting texts and emails and phone calls all hours of the day and night. I am on-call 24/7 and since we started implementing Wide Orbit, the trouble calls have been coming fast and furious. FML.

29JAN2019 - Obstructive Sleep Apnea is the diagnosis. Bad for the heart. Causes depression, irritability, erectile dysfunction. Not so bad on the list of diseases. This is like North Dakota Salsa: extra mild. The GI doctor called to tell me my colon looked good. No cancer, no polyps, no sign of Celiac Disease. So why do I have a fatty liver? Why do I have signs of anemia? I did my week 3 weigh-in for the EDGE six-week challenge, and I’m at 179.6 lbs and 15.6% body fat. Depressing to know that I’m halfway through this challenge and have only lost 1% of my body fat. My goal is to be under 10%. I am confident that I can get there, but it won’t be easy [it wasn’t, and I didn’t “get there”]

29JAN2018 - So much to catch up on. Birthday weekend was great. Went bowling and ice skating with Leah. Ate at Chicago Diner. Wore my crazy kimono-print satin pants, danced at the Whistler, had delicious brunch of Fruity Pebbles french toast. I’ve been teaching some very popular yoga classes recently. I had 25 people in Meditation, 45 in Vinyasa, and 26 in Yin. Larissa [my supervisor] was stoked!

And the BIG NEWS: last Monday, my boss Mike Tompary showed up outside my cubicle and asked me to sit down with him in Don Mueller’s old office. He shut the door as I took a seat, and I felt very nervous right away. He asked “Do you still want the Chief Engineer position?” I had expressed interest in it months ago, but we had pivoted to other candidates, outside hires, and it had been so long since we had discussed it that I was shocked to hear him ask about it. I doubted my own abilities, and told him so: “Well, yes, if everyone here is on board with my shortcomings…” and he said he had just gotten out of a meeting with the station Program Director David, and Network Director Tony and they were on board. Our interim CEO Reese had promised to approve it, “…so, if you want the job, it’s yours!” I stood up and extended my hand, with a big smile on my face. I am Chief Engineer of WFMT. I can hardly believe it. Mike said Al Skierkiwicz would be delaying his retirement for a little while longer so he could show me some of the ropes, and encouraged me to take copious notes as I shadowed him. I am feeling like a rock star lately. Yoga classes going well, work is progressing in a great way, I am in love with a beautiful, brilliant woman. Feeling strong and balanced.

29JAN2017 - My godmother Julie’s son Spencer passed away yesterday. Cancer. He was younger than me, and had two or three young kids. I was following Julie’s Caring Bridge posts, and learned that he had hung on longer than the doctors expected, but it’s devastating to read how such a strong, smart, talented, good man can be decimated by an illness.

Grandma Sauvageau is not doing well either. Her 94th birthday was spent in the hospital. She had taken a fall at home and broke her hip. Lacey visited her at the hospital on her birthday and reported to me that she doesn’t look good. Said Grandma wasn’t aware of her surroundings and looked very weak. Doris flew in from Denver on Friday and Dad flew home from Arizona yesterday. Doris posted a few pictures on Facebook of her kids visiting her. Grandma was awake, but there was worry on the faces of my aunts and uncles in the room with her. I am an imbecile—I spent $1500 on that cheap Chinese double-bass on Friday, when in reality, I should be saving for moments like these.

29JAN2016 - There is time enough for everything, if we allow ourselves to utilize that precious commodity in the correct way. I am feeling very free this weekend after months and months with seemingly no time for my self. This will be my first weekend alone in my new apartment. Today and tomorrow are for me, aside from the small detail of recording WFMT’s Introductions this morning with a 16-year-old violist. I’m excited to get my home in order: do some laundry, unpack a box or two, arrange things, clean and clear out my space. I’ll go for a 6-mile run tonight, then bike tomorrow, get a haircut tomorrow afternoon and maybe take Malin’s Hot Vinyasa class at Lifetime. I have to figure out what the hell to do with my piano though. It kills me that the movers had to leave it outside! In January! At least it’s under the eaves of the detached garage.

Addendum, later that day: Currently sitting at the laundromat down the block because I don’t yet have keys to the laundry room in the basement at my new place. Feeling fried from lack of sleep and ready to pass out already. I shouldn’t have agreed to work this morning, spinning my tires there, wondering why in the world I agreed to give up half my day (a full quarter of my weekend) for net zero. When will you learn it’s okay to say “no”?

29JAN2015 - I have been allowing myself time to “space out” and be bored. My days have been incredibly busy this past month, and I am proud of what I have accomplished. I’ve been giving myself time to work out, time for yoga, allowing copious amounts of time for work. I do feel like I have been spending far too much time on the internet. I miss writing, making music, and social time with friends, but I am reading more. I have been voluntarily unemployed now since the end of September, so I can devote my time to freelance recording gigs and my yoga teacher training. Working on my own schedule was challenging at first, working only about 4h/day for the first week, then 5h/day for the next two weeks, 6 a day for two weeks and I’m now up to 7 to 9 hours each day. I never imagined I could hold myself accountable for this much work. Last week was a little harder as I tried to alter my routine from mornings to afternoons so I could work out and do yoga in the mornings.

I had birthday dinner with Jack Brett last Monday. Among other things, we discussed Jess. I wanted to know if she was doing okay, and he confirmed that she was, but said she was hurt to see some photos of V and me on Facebook. Hard to believe it’s been a year since she moved out. Jack said she is doing better now, and even dating someone who Jack likes, but wasn’t sure how serious they are, stating that they made an arrangement to date “only one day out of every seven.” Interesting…

29JAN2014 -

29JAN2013 - [Facebook post] This ain't no cuppa Joe. It's Cafe Sauvageau. Step 1: Select only the finest Julius Meinl Costa Rican Tarrazu beans. Step 2: Hand grind using mortar & pestle. Step 3: Boil purified water. Step 4: French press that bad boy. Step 5: Commence workday [8 Likes]

29JAN2012 - Mixing some of the Tiger Cry songs today. We’ve been recording this album for weeks in my spare bedroom. Loving the “bee” sound I was able to get from manically strumming a soft percussion mallet along the low strings of my upright piano.

29JAN2011 -

29JAN2010 - My first-ever solo classical recording gig is today with International Chamber Artists!! $75! SWEET!

29JAN2005 - I shall return to the habit of generating my thoughts into this journal. Much has occurred since last I bothered about these pages, but I will come to that in time. We are 16 days into a six and a half month voyage around the world, and July 29th seems like eons afield.

I have been pressured into qualifying ESWS [Enlisted Surface Warfare Specialist] by my chain-of-command. I have been all but promised an “early promote” evaluation if I indeed qualify by March 1st. February shall prove to be either a rude awakening or a new and good beginning for me. Time will tell. We have a list of prospective port calls — all subject to the whims of Mother Navy: Guam in February. Singapore in March. Dubai in April. Bahrain in May. Dubai again in June. Italy in June. England, Florida, and Norfolk, VA in July. Will be interested to see if this route goes as planned (which I doubt) or is altered drastically.

I’ve been planning a budget for music instrument purchases. If I continue to be paid my BAH [Basic Allowance for Housing], I will be able to save quite a bit, of course with that list of ports above, certain purchases may be delayed. I purchased a Takamine 12-string acoustic guitar last Christmas. Mom and Dad just received a brand-new Rickenbacker 4003 bass that I ordered on Jan 6, bringing my tally to:

Dean Exotica Acoustic Guitar - red flame maple, 2000

Danelectro Hodad Electric Guitar - gold sparkle, 2002

Epiphone El Capitan Elec/Acou 5-String Bass - ebony, 2003

Fender Banjo - natural, 2004

Carvin LPF70 Fretless Elec Bass - blueburst, custom, 2004

Takamine 12-string Acoustic Guitar - natural, 2004

Fender Rhodes Electric Piano, 2004

Rickenbacker 4003 Elec Bass - jetglo, 2005

[denotes that I still own these in 2025]

Planned purchases for this deployment include:

Epiphone Casino Electric Guitar ($660)

Musicman Stingray Electric Bass ($1200)

Digidesign 002 recording interface + ProTools recording software ($2200)

Fender American Telecaster ($880)

Ampeg tube bass amplifier ($1500)

[denotes that I purchased these items during this deployment]

I would also like to get an Apple laptop with the ultimate goal having a fully-functional home recording studio paid for and functioning by the time I’m out of the Navy in January, 2007. Less than two years from now, thank Christ.

Several weeks ago, Tim sent me my journal from our previous deployment. I am beginning to fear that it has been lost in the mail. That would be a dreadful scenario, because it contained several musical riffs that I have been working on, poetry that hasn’t yet been transferred to my blue spiral-bound book, and my Westpac 2003 journal in it’s entirety. I do hope it arrives soon.

29JAN1999 - The Malady of One

Introspectively, I wait together,

lessons given, lessons learned,

striving on despite my failures.

Hoping hopelessly her hand inspects the inner,

icicled, whitened walls of winter.

Is the interest homogenic,

hear me?

With she out me, I mean—

I get confused, and

and, I dedicate this simple despair to her

with an aftertaste of embryonic leather.

Apple silence sliced symmetrically,

carefully careless candied comments.

Did you—me—some justice make,

or did I—you—your virtues take?

Rambunctious play reinvents the day:

obnoxious Pythagoras floor-falling.

Irrepressible instincts acknowledging

your presence as the square root of a^2 and b^2.

I just want to die in your embrace,

is that too much to ask?

Allow me to perish near your face,

I’m getting down to bronze tax.

Intestinal infantile blue lights

switch syrupy strength in you,

Your offer of outward exposure

fits into my technicolor torture.

It Happens

Mute sailboats bob at the edge of the earth, like opal pyramids pointing towards Heaven. The vast maw of the lake sucks the sound from the city.

The balance is off.

Here, your mind is a wide open prairie on a smooth spring morning. This is your favorite place: there are no distractions, no work, no phone, no music; only momentum.

You exchange pleasantries with another swimmer as you wade in, knee-deep. “How is it?” You ask her.

“Nice this morning. Not too cold. Not wavy.” She bends an arm back to unzip her wetsuit. “Cops pulled a body out just as I was arriving.”

“What? You’re kidding.” You stand stunned, heels sinking into the silty bottom.

She shrugs. “It happens. Enjoy your swim.”

The city slouches heavily on one shoulder. The low commotion of early morning traffic noise, like a fog that never dissipates, is punctured by the roar of motorcycles or the lamentation of an ambulance. Engines and rubber and tons of steel clatter and rumble along Lake Shore Drive, an eight-lane highway that spoons the shoreline.

On your other shoulder, the soft, quiet pull of a gauzy sky. Lake Michigan is a slate flag undulating in a brisk breeze. The head of a golden retriever glides closer to shore, stick firmly clenched in jaw. Mute sailboats bob at the edge of the earth, like opal pyramids pointing towards Heaven. The vast maw of the lake sucks the sound from the city.

The balance is off.

You wade deeper, pulling the drawstring of your wetsuit zipper up your spine. You fasten the velcro tab at the nape of your neck. You dip your hot pink latex swim cap into the lake and open it up, turn it inside out, then stretch it over your head. The brightly-colored cap highlights your whereabouts for boats and for the lifeguards who will arrive later when the beaches begin to crowd with vacationing families and suburban teens.

Waist-deep, you bend your knees and stretch the rubber collar of your wetsuit to let the lake in. The cold water shocks your flesh. Your heart skips two beats. You spit into your goggles, rinse them, and suction them to your face, inhale deeply and thrust forward. Your arms crawl, pulling you through the lake, legs kick rhythmically, toes pointed to maximize efficiency. Your heart rate spikes. Five strokes, breathe—you open your mouth at the corner to keep from swallowing a wave. Five strokes, breathe—the odd intervals keep you looking at alternating sides.

To your left is the steel-reinforced concrete lake wall, slimy and barnacled. Above it, the Lakefront Path: an artery often clogged by bicyclists, runners, sightseeing tourists, and sauntering downtown workers staring at their phones. Beyond that is Lake Shore Drive and seven-figure condos with floor-to-ceiling windows which glint in the glow of a rising sun. In the afternoon, the skyscrapers cast deep shadows into this stretch of lake. To your right, an empty expanse of harbor. “The Playground” will soon fill with idling powerboats, piloted by spoiled north shore kids. They wear floral-print board shorts and monokinis, and spend hours sipping Old Style or White Claw, flashing toothy selfies for Instagram.

Most days, the lake is cloudy and you can’t see five feet. Here, disaster lurks. Your head is up more than down, looking around for stronger swimmers who might barrel towards you through the din like an eighteen-wheeler rounding a switchback on a narrow mountain pass. You watch for drunks on Sea-Doos, veering too close to shore. You imagine the aftermath: concussed and drowning, no lifeguards nearby to save you. Far-fetched, sure, but possible—it happens.

Today though, the lake is crystalline. In the close hug of your wetsuit, through foggy goggles, you see the downed light post resting on the bottom. You wonder what kind of car wreck launches a light post that far: careening over a guardrail and past a sloping concrete beach, fully fifty yards from Lake Shore Drive. You shiver through a cold pocket and try to regain your rhythm—five strokes, breathe, five strokes, breathe. Garbage litters the rocks, twenty feet below your nose. You see shapeless plastic and metallic things, sun-faded and sand-covered; beer bottles, soda cans, and an entire park district trash can. You spy a solitary fish sucking between stones and debris. It’s a sallow and pitted creature, not even worth a second glance. You become tangled in a fishnet of weeds, so you pause briefly, treading water as you remove them from your face and between your fingers. Your wetsuit buoys you; you bob at the surface like the beacon that marks your turnaround point. You think again about the body. It happens.

The waves push and pull. You gain speed. Your arms are tiring, shoulders burning with the effort. Your neck is raw where you mismatched the velcro. You find your rhythm. You no longer need to count your strokes to breathe. It happens: your body remembers. It’s like writing a letter to an old friend, or fingering a C-major scale on your junior high trumpet.

A pair of swimmers pass you on their way back to shore. You envy the efficiency of their stroke, the power in their arms. You rock gently in their wake. You sneak a peek back—they’re already disappearing into the distance.

You crawl towards the marker, the furthest you’ve made it this season. The waves are getting choppy as you take a wide turn around the beacon and head towards the beach. Eight hundred meters down, eight hundred to go.

The Lavender Silk Shirt

Any minute now, I’d see her round, freckled face, and wavy, messy red hair, as she’d descend the steps. She would skip over to me wearing an oversized Guns N’ Roses t-shirt and ripped jeans, smelling like canned peaches and nicotine. We did it out in the open—never huddled discreetly under bleachers, and certainly not in the blind-darkened, cramped confines of a bedroom, hot and sticky before the parents got home from work: that was unimaginable at thirteen.

I was standing at our spot near the flagpole behind the Dilworth-Glyndon-Felton junior high school, which was just across the street from the apartment I shared with Mom and Lacey. Sarah was running a little later than usual. If she kept this up, I’d miss the start of Animaniacs. After a while, her best friend Misti emerged without Sarah and marched straight over to me. I scrunched my nose to inch my smeared glasses back up. She looked at my shoes, then wordlessly handing me a note, turned to walk away. I unfolded the page:

Hey Josh, it’s been fun, but we both know this isn’t working. Have a good life. xo Sarah.

I read it again.

And again.

I felt like I was riding the Gravitron at the Cass County Fair; centrifugal force pulling my guts into my spine. My eyes clouded with tears as I crossed the street towards home. Breathing hard, I climbed the steps to our cramped second-floor apartment and opened the door, dropped my bookbag onto the floor, sat on the corner of my waterbed and wept, reading the breakup note over and over as tears dripped onto the page, smearing, but not blunting Sarah’s sharp words. It wasn’t even four o’clock when I changed into my green and gold tiger-striped Zubaz and assumed a fetal position under the covers. I slid the note under my pillow and just lay there sobbing.

Mom got home from her undergrad classes at Moorhead State and was making the rounds. I heard her voice out in the living room, “Is your brother in his room?”

Lacey was munching Old Dutch sour cream and onion potato chips and watching Hey Dude on Nickelodeon. “I dunno,” crunch crunch.

Mom paused outside my bedroom, which was just across the hall from the one she shared with Lacey, and rapped softly on my door. “Buddy—?” She turned the knob and slowly pressed it open. “It’s so dang dark in here. Are you in bed already?” My back was to her as I tried to stifle my sobs. “Josh—honey, are you not feeling good?” I had no words, only anguish. Sorrow, like I’d never known before, had choked the voice out of me. Mom sat on the corner of the bed and touched my bony shoulder. “Are you gonna talk to me? Joshua Alan, what is wrong? Did somebody pick on you at school again?” I couldn’t hold it in anymore. Tears soaked my pillowcase as my body shook.

Lacey appeared at my door, cradling the chips in one arm and our five-month-old black and white short-haired kitten in the other. “Zeuser wants to say hi.” She placed him onto the bed, which made little splash sounds as he walked across it.

“Ha-uh, Lacey, that cat should not be on the waterbed. He’s gonna cut a hole in the mattress and then we’ll have a real mess on our hands.” Mom grabbed him and set him, mewling onto the floor. “Ok, well, I’m gonna go get dinner started.” She got up and lingered at my door for a few moments before closing it.

I cried myself to sleep…a knock at my door woke me. “Buddy, I’ve been calling for you, dinner is ready. Get up.”

“I’m not hungry Ma.” My voice was a rusted swing set.

“Well you gotta eat somethin’. You haven’t eaten all day.”

I closed my eyes again and tried to sleep but couldn’t stop thinking about Sarah. What had I done wrong? There was no sign that she was unhappy, just that horrible note.

We met a few months earlier at one of the monthly school dances. The weekend before that dance, Mom took me to Herberger’s at the Moorhead Center Mall to buy me what she called a decent shirt. I wanted to wear my heather grey DGF Rebels tee with my flannel, but she told me I needed to dress up for the dance. I didn’t know what that meant, but as we wandered around the boys’ clearance rack, I was drawn to a silk, lavender-colored, long-sleeve button down. I had never touched material so soft before. The fabric blossomed around the cuffs and the purple buttons gleamed with a mother-of-pearl sheen. Mom crossed her arms in front of her chest when she looked at the price tag, but she let me try it on. I emerged from the dressing room beaming in my huge round-framed glasses. Mom’s heart must have melted to see me smile, because she agreed to pay the exorbitant $29.99 plus tax (marked down from $50).

On the first Friday of the month, the DGF PTA turned the junior high gymnasium into a dance floor, decorated with black and silver balloons and streamers. I stood on the perimeter of the gym, my new lavender silk shirt tucked into my Lee jeans, bobbing my head to “Insane in the Brain”, the bass booming and echoing in the gym. When the DJ played “Epic” by Faith No More, the slow-dancing couples moved out of the way as a small group of headbanging long-haired kids—in torn denim and flannel—overtook the floor. My eye was immediately drawn to a petite girl with the longest red hair who was banging with the best of them. When the song ended, she looked over at me and smiled.

A few songs later, I grabbed a dixie cup of ginger ale and a handful of chips from the refreshment table and was on my way to take a seat on the bleachers, when I got shoved from behind. My chips and ginger ale spilled onto the floor. “Nice silk shirt, puss.” I turned around and looked up to see Travis Motschenbacher, who was wearing a Big Johnson t-shirt tucked into his Girbaud jeans. Travis was in my PE class. He had a build like Superman and a massive tuft of chest hair, which was the envy of all the seventh-grade boys. When I bent over to pick up the mess I made on the floor, he pulled the shirt-tail out of the back of my pants. “Does your mama know you’re wearin’ her blouse?”

Just as I was about to tell Travis to take a long walk off a short pier, the redhead emerged from the crowd and grabbed my hand: “Hey, you wanna dance?”

My heart sprang. “Mmhmm” I nodded as Travis strode off to pick on some other poor sap.

She smiled at me again, tucking a wavy red curl behind her ear, and led me out to the floor. Disco lights skittered across the waxed hardwood as I felt the heat and smelled the BO of my pimpled classmates, pressing up against one another. She wrapped her arms around the back of my neck and I grabbed her narrow hips as we swayed side to side. She took my wrists with her hands, and encircling them around her low back, pulled me closer. She gazed up at me and smiled. Her teeth were lovely: the two top incisors were pushed back just a hint from her eye-teeth, giving her a steamy vampiric glow. My teeth were crooked and yellow, so I smiled with my lips only. I had no clue how to dance. Had no sense of rhythm. She led. Her back was strong and slender and she moved with purpose, with direction. Whitney Houston was singing “Iiiiiiii—will always, love you…” and during the sax solo, Sarah pressed her lips to mine. I could feel the tip of her tongue entering my mouth — almost apologetically at first, but then, as if she was standing on the principal’s desk in muddy Doc Martens, screaming “welcome to the jungle!” I had never given a thought to how a first kiss should feel or when it would happen, but suddenly, Sarah was kissing me. Little sparks started to swirl and blister behind the backs of my eyelids. Our lips locked until the song ended, and then she was waving goodbye as she grabbed her coat and got into her mom’s truck.

Monday morning, passing her in the hallway, she handed me a folded piece of notebook paper, Josh ❤️ scrawled on the front. I opened it: I can’t stop thinking about that kiss. Meet me by the flagpole after school. xoxo Sarah

She came outside, strolled right over to me, wrapped her arms around my neck like she did on the dance floor, and we kissed—long and hard.

That was our whole relationship. Dancing during slow songs. Kissing until the chaperones split us up. Passing little love notes in the hallways whenever we saw each other, and kissing after school. Now it was over though, and so was my life.

When I woke up the next day, I was still in a fetal position. Hoping it was all a nightmare, I reached under my pillow and found the note. I read it and started crying again. Mom swung open the door, “You’re not dressed! Are you planning to play hooky?” I rolled over to look at her before rolling back onto my side and closing my eyes. She slammed the door and I heard her on the phone, telling the school secretary that I was out sick. As soon as I heard the door close, I tuned my clock radio to Y94. “End of the Road” by Boyz II Men was playing through the static, which made me cry harder.

I lay there most of the day, slow jams simmering on the radio in the background. Crying until I had no tears left to spill.

I kept turning over reasons Sarah would do this. Maybe this was like that time with Anthony.

A few months before I met Sarah, Anthony from Social Studies invited me over to his place to look at his stepdad’s Hustlers. I didn’t really know Anthony, and didn’t want to go, but none of my other classmates had ever invited me to their homes, so I figured I’d make a friend. We sat on his couch and listened to his Wreckx-n-Effect tape, and then he told me to grab the Hustler, which his dad kept under the cushion of his Lay-Z-Boy. When I turned back around—without a magazine, because there wasn’t one—Anthony was pointing a .357 at my forehead and screaming “Get on the fucking floor! Give me your money, motherfucker!”

I nearly shat myself and got onto his crusty carpeting as quickly as I could, fingers interlaced behind my head, like I’d seen the perps do on COPS. I started crying, “I don’t have any allowance, please Anthony, I’ve only got some change in my pocket, please, please, don’t do it!”

Anthony started laughing maniacally. “Get up, man. Get up. I was fucking joking, man. I wasn’t going to rob you, bro, haha. It was a joke.” He buried his stepdad’s gun in the cushions of the couch and patted me on the chest. We watched an episode of America’s Funniest Home Videos and then I walked home, never breathing a word of that joke to mom.

Maybe Sarah’s note was just a joke.

Mid-afternoon, Lace got home from school, singing “Joshy! I’ve got your homework.” She came into my room, munching Cheetos, and tossed my assignments onto the bed, then skipped back to the living room to watch TV. I took a peek at the pile of homework, then swiped it onto the floor with the back of a forearm. Go to hell, Mrs. Anderson: what can a dissected pig brain teach me about loss? Give me a break, Mr. Vossler; unless your dovetail joint can mend a broken heart, I have no use for it.

I got out of bed to retrieve the cordless phone, squinting as the streaming sunlight stabbed my eyes. I locked the bathroom door behind me and sat on the toilet, pressing Sarah’s digits into the phone—for the first time, I realized. “Hello?” an adult woman’s voice answered. Her mom? An older sister? I didn’t know anything about her family.

I had no idea what I was going to say to Sarah. “Take me back?” “I’m drowning on tears?” Maybe she was waiting for me by the flagpole right now, and it was all just a misunderstanding. “Hi, is Sarah there?”

“Who’s calling?”

“This is Joshua.”

“Sasha?”

“No, Joshua—”

Sarah’s mom/sister placed her hand over the receiver and shouted “Sarah, do you know a little girl named Sasha?…” Silence, then a dial tone.

I re-dialed the number. The same voice answered. “Hello? Uh Sasha, yes, she’s…not home from school yet, but I’ll let her know you called.” Dial tone.

Sarah had cracked open my ribcage with her painted black fingernails, and like the metalhead she was, devoured my entrails over a nasty, wailing, Slash guitar solo.

Mom got home from class and marched straight to my room. “Still in bed?” silence “Maybe I’ll just call your father and tell him that you won’t talk to me.” I couldn’t look at her. She wouldn’t understand. I just pulled the comforter over my head. “Have you eaten today?” silence “You better pick up that homework or Zeus is going to use it for a litter box.” silence

The second night was a carbon copy of the first. I continued rotting in my bed, rooting around in stale pajamas, re-reading the note.

The following morning, Mom tried to pry me out of bed again, but I still refused to move, refused to speak. She popped her head into my room on her way to classes. “I’m calling you out sick one more day, but this is really it. If you’re not out of that bed by the time I get home, I’m gonna take you to the emergency room, buster. Is that what you want? Get the doctors to poke and prod you? Eat something and clean the litter box as long as you’re not doing anything constructive.”

I wondered what Sarah would think of me missing school two days in a row. Did she care? Did she even notice? My ears burned as I imagined her and her headbanger friends roasting me over lunch, laughing so hard that Jolt cola sprayed out of their noses. Sarah would probably be making out with some other boy after school today. Maybe Ted Mars: he was not only taller and better looking than me, but he played drums in Doomslayer and was, like Sarah, a grade older than me. They’d be graduating middle school in a few weeks and going off to DGF High School, which was miles away in Glyndon. Happily ever after.

I leaped out of bed, flung open my closet door and pulled my lavender silk shirt so hard that it snapped the cheap plastic hanger. I sniffed the front of the shirt, hoping I could catch a whiff of Sarah, from the last time she pressed her cheek to me. Nothing. It smelled like me, like my clothes. I sat back on the edge of my bed and buried my tears in the shirt. I felt like a vase—that once held a fragrant bouquet of wildflowers—now empty, cracked, and tossed into a dumpster. My thread to Sarah was a tenuous one, to be sure, but now nothing remained, save a wrinkled, tear-smudged break-up note. I pulled the note from under my pillow one last time, re-read the words which had been indelibly etched into memory and tore the page into funeral confetti.

I didn’t even notice Mom standing in the doorframe of my bedroom, her shoulder slouching under the weight of her bookbag.

“Mom—” I dried my eyes with the back of my hand, “how long have you been standing there?”

“You’re gonna stain that shirt.” I tossed it onto the floor and expelled a tear-shattered shudder. She joined me on the padded railing of my waterbed. “Buddy, you know you can talk to me about anything dontcha?” She angled her head to make eye contact with me, put her hand under my quivering chin. “I’m your mother.” I nodded my head and sniffled. She put her arms around me and hugged me tight, gently patting my back like she would have done countless times when I was an infant. “What’s her name?”

I stiffened.

“This little redheaded gal I saw you kissing across the street; did she do this to you?”

“…Sarah.” I was gobsmacked. How long had she known?

“Ta heck with this Sarah. It’s her loss. Joshua, I know you don’t wanna hear this now, and you prob’ly won’t believe me, but there will be other Sarahs down the road. You are gonna meet so many girls, boys, whatever, in your life and some are gonna hurt ya, and some you might hurt.”

She was right. I didn’t believe it. Didn’t want to. I shook my head.

“It’s true. But they’ll all become a piece of you: the good and the not-so-good. Though they may never meet in real life, they’ll live side-by-side in your heart.” She interlaced her arthritic fingers to show me.

I turned my head to see Zeus curled up and purring on my lavender silk shirt.

Mom held onto my narrow shoulders and looked at me through my smeared glasses. “But ya can’t give up. We’ve just gotta keep going. Ta heck with this Sarah. It’s her loss. Now, let’s get you some mac n cheese, huh? You’re about to blow away in a stiff breeze.”

I nodded and followed Mom to the kitchen.

You Can Tell an Awful Lot About a Guy from the Shape of His Vehicle

I ran the Avalon into the ground one month after quitting my day job as a government bureaucrat. I rode the Amtrak back to Fargo to explain myself to Dad. I was rambling, like usual, trying to tell him why it was so important for me to leave a good paying job — with benefits — to sign up for Yoga Teacher Training.

Dad and Grandad conspired to surprise me with my first car when I was fifteen. Under Dad’s guidance, Grandad scoured the Fargo Forum classifieds for weeks looking for a practical used model. Grandad must have loved this — in retirement, he made a hobby of buying inexpensive used vehicles, fixing them up, and reselling them to make a bit of money. Every time I saw him, he was driving a different car. Ultimately, he and Dad made a decision together and finalized the sale.

We were living in Minot at the time, and Dad somehow enticed me to spend a weekend traveling to Fargo with him. I was in my punk phase then: pink hair, pleather pants, safety pins in my ear, studded dog collar. At fifteen, I didn’t have time to go visit my grandparents. I was too busy plotting the important details of my immediate future. My band, The Atomic Snotrockets, had an upcoming gig, so I needed to rehearse on Friday night. My heavy-petting partner and I were getting together to watch X-Files on Saturday. There was homework to cram in at the last possible moment Sunday night. Nevertheless, Dad coerced me to ride along for the five-hour drive from Minot to Fargo. We pulled up to Grandma and Grandad’s place. Parked in front of the house was a robin’s egg-blue ’84 Volkswagen Golf with vanity plates: 4-BUDDY, my parents’ nickname for me. There’s a photograph somewhere that Grandad took of me opening my car door for the first time. I have a huge grin on my face. I never smile in photos.

Six months later, Mom came downstairs and tapped on my bathroom door as I was getting ready for school. “Buddy,” her voice wavered as she laid a hand on my shoulder and told me that Grandad had died in his sleep. I felt my knees tremble. “I think your dad could really use a hug right now.” It was the only time I have ever seen Dad cry.

Seven years after Grandad passed, I was living in Charleston, South Carolina, and getting ready to move to the west coast. Dad flew down to help me make the cross-country road trip. I had plans to trade in my purple Chevy Cavalier for an Acura Integra coupe. It was a sexy, silver two-door with a spoiler. The interior leather was glossy and black. It had a five speed on the floor and a booming sound system with a Rockford Fosgate amplifier and two twelves in the trunk. Dad calmly guided me towards a more practical choice: a forest-green, four-door Mazda 626. It was the polar opposite of the Integra. The interior wasn’t shiny black leather, but boring beige polyester. No sound system — not even a CD player. The 626 had a stock AM/FM tuner and a tape deck.

Dad and I drove the 626 from the South Carolina Lowcountry to the Puget Sound, where I would live for three years. I drove the Pacific Coast Highway from Seattle to San Diego and back in that car, windows down, playing the mixtape I made specifically for the journey. I folded down the back seat and slept in the 626 along the side of the highway there in the shadows of the towering redwoods near Crescent City. I made a second cross-country trip in that car when I moved to Virginia Beach in 2005, and put more miles on it when I finally settled in Chicago in 2007.

The 626 was the only car I ever paid off. I remember getting the title in the mail from my bank, after paying off the loan. The paper was ivory card stock, with purple purfling in the margins and an official-looking watermark from the bank. I framed it and hung it on the wall. Eventually, the transmission went out and I had to have it towed to a junkyard.

After Dad retired, he started wheeling and dealing used cars. An expert haggler, he’d buy them for cheap, fix them up a bit, and resell them for a slim profit. These were not major overhauls; he wasn’t investing in dilapidated ’57 Chevy Bel Air hard-tops and restoring them. He’d buy dependable, modern cars which had a track record of longevity: Camrys, 4Runners, Civics. He would detail the tires, wax the hood, Armor-All the seats. It was a hobby.

A while after my 626 broke down, Dad surprised me by showing up in Rogers Park. I was celebrating my third year in Chicago and it was the first time he ever visited me there. The second and final time would be for my wedding. He pulled up in a used 2002 Toyota Avalon and handed me the keys. I couldn’t believe it. I drove that car for four years. I could never tell if it was grey or light blue; its color was mercurial, like Lake Michigan. Avalon — it reminded me of that Roxy Music song of the same name. I could almost hear Bryan Ferry singing it — and your destination…you don’t know it.

At some point, the Avalon’s trunk latch broke and I had to keep the lid tied down with bungee cords or it would fly up while driving. One headlamp burned out and I never got around to replacing it. The check engine light was perpetually on. Then one day, the low oil warning light lit up on the dashboard. Dad had taught me to check my oil each time I filled up the gas. I didn’t, of course. After a few days of this light staying on, I bought a quart of oil and poured it in. Things would be okay for a week or two when the light would come on again and I’d repeat the process. I tried to remain optimistic, but my stomach twisted every time I started the car and saw that ominous light on the instrument panel. I was recently unemployed, and couldn’t afford to pay an ungodly sum of money to fix it, so I kept buying a quart of oil at a time and pouring it into the car. One day I flicked the ignition switch and it wouldn’t turn over. The low oil light had been illuminated for several weeks by then. I shouted in frustration and pounded on the steering wheel. I had it towed to a nearby mechanic where they told me the oil pan had cracked which led to the engine seizing up because it wasn’t getting the regular oil supply it needed. CarMax gave me two-hundred bucks for the vehicle. They told me they were going to “part it out”.

I ran the Avalon into the ground one month after quitting my day job as a government bureaucrat. I rode the Amtrak back to Fargo to explain myself to Dad. I was rambling, like usual, trying to tell him why it was so important for me to leave a good paying job — with benefits — to sign up for Yoga Teacher Training and pursue my nascent, albeit outlandish dream of opening a non-profit yoga studio for veterans. He didn’t bring up the Avalon, but he looked worn out. “What about saving for retirement, Son?”

“Retirement!” I scoffed, “My generation doesn’t get to retire.”

Later that week, I hailed a 2 a.m. cab to the Fargo Amtrak depot to wait for the Empire Builder line to Chicago. I had just taken out my pen to work on some YTT homework when the depot’s lobby door swung open. I was dumbfounded to see Dad walking towards me with a thermos at three in the morning.

“I thought you could use a coffee,” he said. “Hold this. I’ve got something in the car.” He carried in three bags of groceries for my twelve-hour journey. Alongside the bananas, granola bars, and bottles of Vitamin Water, he had picked up a fresh six-pack of Hornbacher’s Peanut Butter rolls — my favorite treat from back home. He sat down next to me and opened up his wallet, handing me several bills. “Here. I want you to take this for the trip, in case you get hungry.” I shook my head, but I knew refusing was impossible. We chatted there for about an hour until I had to board my train. As the Empire Builder lurched forward, I watched, with tears in my eyes, as Dad got into his clean, always-properly-maintained truck and drove away.

My Ass Rides In Naval Equipment

I should’ve just gone over to the house for this conversation, for Christ’s sake. I only lived a mile and a half away.

I had been staring at the cordless phone in the corner of my cramped bedroom for over an hour, cracking my knuckles and scratching my hairless chin. Finally, I closed my eyes, took a deep breath, and pressed the digits into the keypad.

One ring… two rings… Maybe he’s not home… three rings… A wave of relief started to wash over me. I couldn’t leave this in a message, but this will give me more time… four rings… Yello! A familiar voice warmly barked.

Hey, Dad. My heartbeat thundered in my throat. How’s it going?

Just finishing up my lunch break, Son. What’s up?

I should’ve just gone over to the house for this conversation, for Christ’s sake. I only lived a mile and a half away. Sweat rolled down my rib cage. Well, Dad, I just wanted to tell you…

Three months after graduating high school, I decided to get my own apartment. Not because our home was crowded. Not because my family and I didn’t get along — we did, at least as well as parents get along with their teenagers. Deep down, I think I wanted to prove to them that I could make it on my own, even if that meant working seventy hours a week as a night stocker at Marketplace Foods and a Whopper flipper at the Dakota Square Mall food court.

Most of my co-workers at the mall Burger King were high schoolers or recent grads like me. Karen Knudson was in her mid-fifties. She was a farmer’s daughter. In her teens, Karen married a neighboring farmer. They had several children who helped out on the family farm. In Karen’s mid-fifties, with the child-rearing over and the farmwork passing down to her adult sons, she decided to trade her pig whip for a french fry scoop.

It came up in conversation one Saturday after the matinee rush had ended and the food court was clearing out that Karen had never traveled outside the borders of North Dakota. What do you mean? I sneered, loosening my spiked pleather dog collar, Not even on vacation?

Karen folded her arms in front of her grease-stained apron as she waited for Order 456 to retrieve his Double Whopper with cheese meal. Nope. You can’t go on vacation when you have cattle to mind and fences to mend. She squinted at me like she wanted to say something more but held her tongue.

I regarded her over the top of my Buddy Holly-framed, yellow-tinted glasses, So you’re telling me you’ve never been outside the state? Not even once?

At a tender twenty, I had traveled beyond the borders of my home state, but never far. Dad’s idea of a vacation was spending a long weekend at Gram and Grandad’s fishing cottage in western Minnesota or hunting pheasants in northwest South Dakota. I once took a day trip to Winnipeg to shop with a high school girlfriend. But honestly, in fifty-something years, Karen had never been outside the borders of the Prairie State?

As I was throwing Karen a pity party she didn’t ask for, her beller brought me back to reality. Josh! I’m still waiting on that King-sized french fry!

This information ate at me over the ensuing days. During my night shift at Marketplace Foods, I spilled Karen’s guts to Nat Tanu, the Nepalese stock clerk with one hand. On hearing the news, he turned to me, eyebrows raised, box-cutter clenched between his teeth, and gasped “REALLY?” before dropping a jar of sauerkraut on the floor. It shattered instantly, raining down a hellish odor of rancid cabbage and vinegar so potent that Rob from produce ran over to see what the stench was.

Really.

I had no intention of living in North Dakota my entire life, but I had no exit plan either. Joyce, the gal I was dating at the time, wasn’t that into me. In fact, while I was helping Nat mop up the sauerkraut spill in aisle four, she was banging my best friend Ricky in the back room of his mom’s trailer home. At the time, I was living vicariously through my older sister, Lara. She had interned for a congressman in Washington DC, crashed for six months on a houseboat in Barbados, and at times called Colorado Springs, San Diego, and Whidbey Island home. I wanted a life like that.

My career plan was an enormous question mark. I envied classmates who had their undergrad, graduate, and even post-grad education already plotted out like stars in the Big Dipper. I had successfully finished two semesters at Minot State University but hadn’t yet declared a major. How was I supposed to know at twenty that a career in Arts Administration or Music Ed would still challenge and fulfill me at sixty?

I spent a few restless weeks ruminating over Karen’s situation. One day, during my half-hour lunch break, buzzing on NoDoz and Surge to keep awake, I followed my feet to a sleepy corner of the Dakota Square Mall. The Armed Forces recruiting offices were all dark and deserted on that weekday afternoon, with the exception of the Marine Corps office. I didn’t go in. I stood outside the office, admiring the sharp royal blue uniform on the mannequin in the window — the brass globe and anchor gleaming at the collar points, the blood-red stripe down the pant legs, the pristine white gloves on the mannequin’s hands — and I caught a glimpse of my reflection in the glass. Spiky hot-pink hair jutting out from under my BK visor. A silver hoop perched in my left eyebrow, two gold studs in my right ear, a safety pin dangling from the hole in my left. My purple polo shirt with the Burger King logo stitched into the breast was filthy, reeking of stale grease: an odor that never washes out.

I reached for one of the recruitment pamphlets and pretended to read it until one of the Marines came out to greet me. The recruiter scanned me — toe to tip — with a puckered mouth. His ramrod posture made me stand up a bit straighter. You ever consider signing up, kid? The Corps will make a man of you. I could see my reflection in the polished gloss of his boots.

Hmm, I don’t know. My dad was a Marine. Two tours in ‘Nam. Late sixties. Da Nang. I didn’t talk like this; Dad did. His history was sneaking through my squeaky windpipe.

The recruiter’s deeply sunken eyes were laser-focused on my ear lobes. No shit? Tell your pop Semper Fi. I can get you some more reading material if you’re curious. He shoved a few tri-fold pamphlets into my soft hand. I nodded to him, and as I turned to leave, he stopped me. Woah woah! Wait a second, kid. I turned around as he approached me. The creases in his khakis were sharp enough to draw blood. About face! he ordered. I stared at him blankly. It means turn around. Turn around…please. I felt him tug my shirt collar down. Plunging a fat finger into the back of my neck, he whistled. Ooh wee, what in hell did you get that tattoo for? I chuckled, getting ready to explain its origin when he cut me off. Sorry, kid. The military’s a no-go for someone with a visible neck tat. It’s against UCMJ regs.

UCMJ…? I trailed off. Oh well, it was a dumb idea anyway.

As I walked back to finish my afternoon shift, I could feel my face reddening and a damp warmth spreading across my upper back. My heart was fluttering from the massive dose of caffeine I was on. Back at work, I went into the deep freeze alone and pummeled a box of frozen Whopper patties until my knuckles bled, thinking about that shriveled, insulting jarhead. For perhaps the first time ever, I was feeling self-conscious about my life choices.

The seventy-hour workweeks were grinding me into a coarse powder. My roommates Brock and Dave were on another planet. I would come home completely exhausted from back-to-back shifts to find them throwing marijuana parties. People were over day and night, watching action movies in my living room or playing electric guitar in the basement. Once, arriving home and desperate for rest, I found a girl I didn’t know passed out on my futon, half-naked, in a puddle of Coors Light.

The summer marched ceaselessly onward. I was still popping caffeine pills and barely functioning at either of my jobs. Was it night or day? I rarely knew. After a closing shift at Burger King, followed by an all-nighter at the grocery store, I woke up in a flop sweat, yanked my smelly BK uniform out of the dryer, and sped up the 16th Street hill, the summer sun slanting at an unnatural angle. I parked the Civic hatchback, ran through the restaurant’s back door, and punched in. I apologized to my assistant manager for my tardiness.

Josh — what are you even doing here? Jolene wiped cookie crumbs from the corner of her mouth and pulled the schedule off the wall. You’re not working until eight.

Yeah, it’s 8:20, Jolene! She shook her head and showed me the schedule.

Eight AM! As in tomorrow morning! My head was spinning. Jolene cackled at me. Go home and get some sleep, Josh.

I looked at my watch. There was no time for rest as my grocery store shift was starting in under two hours. I hopped back into the Civic and drove a mile to the outskirts of Minot. I looked out at the endless prairie: knee-high tan grasses, dusty gravel roads, a fumey combine. I saw quiet railroad tracks and listened to humming power lines.

I didn’t see a future. I wanted to smell the ocean. I wanted to feel the rumble of a subway under my feet. I wanted to run.

The next afternoon, finally drifting into the sleep of utter exhaustion, I thought about a book I hadn’t seen in years. It was a hardbound boot camp yearbook Dad showed me once when I was in grade school. A striking, strong young man in short sleeves and cargo pants burst out of the book’s glossy black and white pages: marching in ranks, posing with an M-16 in a helmet and head-to-toe camo. Seven-year-old me looked skeptically back and forth between the images Dad pointed to and the man before me who was in his mid-forties and balding with a beer gut and a bushy salt and pepper beard. That’s me poundin’ the hell out of some poor sum’bitch with that big damn, oh whatchu call it, Joust? Baton? Some damn thing. Oh, and here’s me again, going over that obstacle course wall at Camp Pendleton… he nodded. Now, wouldn’t you want to be a Marine, just like your Pop someday?

No, I flatly told him. I want to stay at home and cross-stitch with Mommy.

Mom cheered and bent down to squeeze me. That’s my boy!

Dad sighed deeply and tucked away the book.

Dad’s time in the Marine Corps was something I was aware of but never openly discussed. Like Dad’s memories from those years, that book would remain locked up in his varnished oak gun cabinet for most of my youth, next to his twelve-gauge Remington and a thirty-ought-six.

Grandad was in the Army Air Corps in World War II. My uncle Arlo was a Marine pilot in Vietnam and another uncle, Larry, was a Vietnam vet who served in the Navy. My sister Lara was in the Air Force National Guard, and my brother-in-law Tim was a Navy yeoman. As a straight edge, anti-authority, hardcore punk kid, I had never even entertained the option of a military career.

My high school years were turbulent, and there were many times when my behavior was outright humiliating. Like when a girlfriend and I — bored and wielding Sharpies — graffitied the entire ceiling of my first car with colorful phrases like “no war but the class war” and doodles of dicks and daisies. Dad took away my driving privileges for two months after that stunt.

Or the night when Dad went into a closet in the basement looking for his winter hunting clothes and discovered a gravestone that read DAD. My bandmates and I thought it would look “punk as fuck” as a prop on stage at the next Atomic Snotrockets concert. The following day, a yellow sticky note was affixed to my bedroom door: “Son, no questions asked. Get RID of the headstone! — Dad”.

Then there was my cricket farm, nipple piercings, screamcore rehearsals in the basement… Maybe it was the Hail Mary of redemption, but the hope of winning Dad’s pride held extra sway over my decision. The next day, I walked with urgency back to the recruiters’ offices, hoping the Marine had the day off.

He did. I proceeded to the Navy recruitment office. I asked the sailor behind the desk if neck tattoos were allowed in the Navy. He dropped a half-eaten Big Mac onto his paperwork-strewn desk and slid it away. Let me take a look, he said. As he approached me, I could see greasy thumbprints smearing his spectacles. That? That’s nothing. Your shirt collar would hide most of it. He wiped his hands on his wrinkled uniform pants. Take a seat, young man. You ever heard of the ASVAB?

A few days after taking the military entrance exam, the recruiter called me up. Congratulations. You did well enough on the ASVAB to be a Nuke if that’s what you want. I had no clue what that meant or what I wanted. I said yes. He told me the next step was enlistment. As soon as next week, I could raise my right hand, swearing an oath to support and defend the Constitution of the United States. He asked me to think about it.

I thought about it. I didn’t discuss it with anyone else. My future started to crystalize over the next few days. I could leave North Dakota. I could have money for college, and since I didn’t know what I wanted to major in, I’d have time to think about it. I could continue the family military tradition. Dad might be proud of me.

So there I was, calling to give Dad the news, rather than just driving a mile and a half to the house.

Well, Dad, I just wanted to tell you…that I’m enlisting in the Navy next week. Silence. I pressed my ear to the receiver. Had he hung up?

Dad…?

Uh, say that again, Son? To hell are you talking about?

I told him the whole story about first meeting the Marine recruiter and getting rejected. Thinking about it, going back, speaking with the Navy recruiter, and taking the ASVAB. I told him it made sense since I would get good experience and money for college. I didn’t tell him about the pride.

Have you told your mother yet?

No, Dad, I thought you could break the news to her.

Oh yah, he laughed. Thanks a lot! I couldn’t read him. I should have just gone over to the house. Well, Son, I never thought I’d live to see the day where you joined the military, but I always thought if you ever did enlist, God help you if you joined the Marines. Pick the Navy or Air Force. They don’t do a goddamn thing anyway. Safer.

I laughed. Yeah, I guess.